Currency Exchange: Staging Aristophanes’ Wealth in New Orleans

Karen Rosenbecker and Artemis Preeshl

Loyola University New Orleans

Introduction

At the heart of Aristophanes’ last extant comedy, Wealth (c. 388 BCE), lies a set of uncomfortable questions about the nature of economic inequality: “Why do the rich keep getting richer and the poor keep getting poorer? Why is it so hard to get ahead, no matter how hard I work? Why do I get punished for playing by the rules while others get rewarded for breaking them?”1 Although Aristophanes raised these issues of poverty and equity in another millennium, they are still decidedly current and universal concerns. Given socioeconomic events in the United States surrounding the Great Recession of 2009, and a series of well-publicized disasters in New Orleans from 2005–2013 (as well as the power of theater to frame the aftermath of catastrophe and to represent the complex and painful connections between those who suffer and those who prosper), we felt that a staging of Wealth in New Orleans had much to offer to a contemporary audience.2 In January 2013 we had the opportunity to translate and adapt Wealth as part of the spring schedule of performances presented by the Department of Theatre and Dance at Loyola University New Orleans. The production aimed to take Wealth into a modern setting, using post-Katrina New Orleans—and post-Great Recession America in general—as a backdrop for exploring the problematic moral and economic questions posed by the original. This article is a discussion of our production choices in translating and adapting Wealth and in mounting such a production with a student cast and crew, and for a predominantly student audience. Thanks to talk-back sessions and post-production surveys of various student groups who saw the play, we can also address how our production choices were understood and appreciated, and what the students’ reactions might suggest about working with a genre as particular and peculiar as Old Comedy at an undergraduate level.

Background on Aristophanes’ Wealth

Wealth begins with two men, the farmer Chremylus and his slave, Cario, following at a distance behind a blind and shabby hobo. Unsurprisingly, when the pair asked Delphi to explain the unfair distribution of wealth, the response was not an answer to the paradox of the inverse relationship of moral merit to material reward, but rather an injunction to “follow the first person you meet.” As it turns out, the hobo is none other than the titular god of Wealth, who has been blinded by the malice of Zeus and condemned to wander the mortal world as the victim of greedy and corrupt men. This mishandling of Wealth explains the poverty suffered by decent men, but it also hints at the solution: healing Wealth will allow him to shun the wicked and visit the good, thereby equitably sharing wealth in all its forms. To this end, Chremylus and Cario enlist the help of a chorus of farmers and their skeptical neighbor Blepsidemus in order to fight off the goddess of Poverty, to trick Asclepius, the god of healing, into assisting them, and to frustrate a series of interlopers bent of delaying or derailing the financial realignments. In the end, although the main characters are enriched beyond their wildest dreams, questions regarding the fairness of the redistribution of resources remain unanswered, and we are left with the unsettling conclusion that Chremylus and his allies may have simply transferred wealth, rather than shared it.

For those familiar with Aristophanes’ comedies, a poor man employing a crazy scheme to achieve world-altering results is the expected structure for the plays. But what makes Wealth unique is its subject matter and focus. Throughout Wealth, Chremylus is not beset by a figure of political or social importance, nor by the ravages and disasters of war;3 instead, his antagonist and the catalyst for change are what occur in the wake of such things. The impoverished conditions common to most of postwar Greece and the universality of Chremylus’ questions to the oracle allow Wealth to speak not only to the situation in Athens, but to that in other cities as well.4 Throughout fourth-century Greece, the economic and social upheaval caused by the Peloponnesian War continued well after the formal cessation of hostilities in 404 BCE, with many cities suffering from endemic poverty, ongoing food insecurity, and a chronic lack of basic material goods.5 Conditions were so grim that protestors advocating debt forgiveness rioted in the city of Argos, even going so far as to attack rich citizens; several of their victims were beaten to death.6 In Athens, the speechwriter Lysias wrote of the public anger aroused by rumors that certain grain dealers were manipulating wheat prices for their personal gain.7 By the middle decades of the fourth century, the Athenian economy had become so bad that the city needed to subsidize the price of theater tickets through a fund called the theorika, so that all citizens could attend the City Dionysia.8 This level of impoverishment had its greatest impact on farmers like Chremylus, who were the majority of the population. For average citizens like him, whom we envisaged as the ancient equivalent of “the 99%,” the beginning decades of the fourth century were hard times indeed.

Post-Great Recession America, Post-Katrina New Orleans

This chronic and widespread economic distress in Wealth was our initial point of connection between ancient original and modern adaptation. In millennial America, the financial catastrophe created by the bursting of the housing bubble in 2006 and the subsequent economic stagnation of the Great Recession—the effects of which have extended well into 2014—provide a contemporary context and parallel to the ongoing poverty of fourth-century Greece. Likewise, the upwelling of public anger as exemplified by the traction and longevity of the Occupy Movement,9 an international grassroots protest movement begun in 2011 and focused on addressing income inequality, and the infuriating perception that wealth is still being transferred into fewer and fewer hands,10 create a modern counterpart to the expressions of citizen anger preserved by Diodorus Siculus and Lysias.

Just as the Athens of Wealth may “stand in” for many other cities in fourth-century Greece, so too we felt New Orleans was particularly suited to be a modern locus for a discussion of civic suffering. Although Hurricane Katrina made landfall in August 2005, the recovery of New Orleans is still playing out some ten years later. During the years after the storm, the culpability of the Army Corps of Engineers in failing to maintain the federal levee system, the mismanagement of aid efforts by FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency), and the inefficiencies of the various state and local recovery programs have all been well-documented and ongoing problems for the city. Between 2010 and 2013, several other events created another round of problems for the residents of New Orleans. In, 2010, the Deep Water Horizon Oil Spill not only harmed the Gulf’s fragile coastal wetlands, but also profoundly affected the commercial fishing industry in the region and damaged consumer confidence in Gulf-sourced seafood. In 2013, the “Mother’s Day Shootings”11 saw gang tensions erupt into a gun battle at a neighborhood parade, leaving four spectators dead and 20 injured. That same year, a series of indictments for graft charges were brought against Mayor Ray Nagin; convicted on 20 of 21 counts, Nagin will probably face up to ten years of jail time as a result.12 Such events have harmed more than New Orleans’s economy, infrastructure, and housing stock; these social tragedies draw negative attention in the media and alter public perception of the city. Across the nation, there is a sense that New Orleans “can’t seem to catch a break,” and that perhaps its famous epithet, “The City that Care Forgot,” has now acquired a grim, second meaning.13 Despite economic and civic malaise, theater in post-Katrina New Orleans has provided a unique environment for connecting issues facing the city—and increasingly the nation as well—with questions asked by playwrights many times removed from post-millennial New Orleans.14 In staging Wealth, we wanted to be part of that conversation by adapting the play so that it highlighted the parallels between the economic chaos onstage and the economic chaos in “the real world,” with New Orleans serving as a setting but also acting as a representative for any city suffering the economic downturn.

City Dionysia and Mardi Gras

We also made the choice to set Wealth in New Orleans because of the strong parallels between the culture of dramatic festivals in Athens and Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans. For both cities, these rituals are much more than religious rites; they may also serve to express their city’s collective concerns and convictions. The idea that Athenian theater and civics were related is not a new one, but in recent decades classical scholarship has revealed the extent to which Attic drama mirrors the institutions of the polis.15 Old Comedy in particular features a level of topicality and immediacy in its commentary that tragedy, which speaks through the veil of myth, cannot. In addition, the privilege of self-assertion and license enjoyed by Aristophanes’ characters offers them the opportunity to directly criticize and actively challenge aggravating circumstances and individuals within their city,and in so doing to create sweeping changes.16

The connection between Mardi Gras parades and social commentary is perhaps not so well known. The tradition of Mardi Gras krewes creating individual floats or even shaping their whole parade to comment on the “state of play” in New Orleans is a tradition that dates back to the founding of the Mystick Krewe of Comus in 1856 and continues through the modern era. Krewes are capable of stinging and focused social commentary; in 1877, for example, the Krewe of Momus produced an entire parade, some 20 floats, entitled “Hades: A Dream of Momus,” which represented the city as the Underworld in order to criticize the waste and injustices associated with the Reconstruction-era government. More recently, Krewe D’Etat, as part of the 2006 Mardi Gras, which fell approximately six months after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city, produced “d’Olympics d’Etat,” a parade theme meant to allude to the political game-playing that the city endured during the immediate aftermath of the storm. One of the lead floats, entitled “Welcome to the Chocolate City,” seized on Mayor Ray Nagin’s infamous “Chocolate City” comments,17 casting him as Willie Wonka-like figure; the float also featured visual elements depicting the city as his mismanaged Chocolate Factory and was emblazoned with graffiti based on other perceived gaffes the mayor had made during the disaster.18 Other floats extended the criticism of President George W. Bush and FEMA director Michael D. Brown; one float in particular, titled “Homeland Insecurity,” played off Bush’s then praise of Brown for doing “a heck of a job.”19

Also integral to the nature of Carnival Season in New Orleans and theatrical rites in ancient Athens are the elements of engaged spectatorship and of inversion of social norms. In this respect, Mardi Gras is a remarkable modern parallel to the City Dionysia; these festivals represent a moment in which the cities cease civic business and engage in celebratory activities that include public spectacle and private parties but which have, at their center, performances featuring masked, role-playing participants and entailing a high level of participation on the part of their audiences. For the re-presentations of Mardi Gras in Wealth to have the greatest effect, we ran the play through Samedi Gras (the Saturday before Fat Tuesday), to give our student cast, crew, and audience the opportunity to attend a parade before they saw the play. At all parades during the Mardi Gras season, interaction between the riders on the floats and the parade-goers is both encouraged and expected. Yelling and begging for throws (e.g., strings of beads, colorful plastic cups, small toys) from the riders is such an ingrained tradition that many locals joke that their first words were “Throw me something, mister!” Crowd interaction goes beyond simply asking for throws; many spectators don costumes of their own, some dance and perform on the sidelines of the parades, and even the police are not immune from joining in. Certain set floats, which are fan favorites, are a cue for spectators to turn the tables on riders and toss throws back at the floats. It is also not uncommon for riders and spectators to change roles as the parade schedule unfolds; riders in one krewe enjoy their elevated, enriched status during their parade as they shower the spectators with “wealth,” but later they become spectators at other parades, joining the “poor” crowd in begging for throws. In this way, the change from rich to poor, and poor to rich, plays out on the streets of New Orleans in a manner than is not only highly participatory, but also mirrors the shifting status of characters in Wealth.

“Parade Culture” and Metatheater

In our production of Wealth, we used these traditions of the New Orleans “parade culture,” the traditions of crowd interaction and participation that are ubiquitous during Mardi Gras festivities, to create a sense that the staging was something very like a parade, an event that—like Aristophanes’ original—was conscious of its own theatricality, that was full of satire and mockery, and that blurred the line between actor and audience. Characters in Wealth spoke openly of their “director” and “writer”; they referred to the “sound techs” and occasionally looked off to them when a cue was unexpected or absent; moreover, we gave the actors directions to interact with the audience at certain junctures. Taking full advantage of the L-shaped seating arrangement possible in a black-box theater, we instructed Wealth upon her initial entrance to stumble into the front row of seats and touch audience members. We had Hermes step out of the action and ask an audience member for his/her program so that he could look up Carry’s name. During the agon, we directed Inida and Poverty to speak the bulk of their lines directly to the audience, as if they were at a town hall-style debate. And as the play moved towards its conclusion and the onstage world was enriched, Carry tossed an increasing number of Mardi Gras doubloons to audience members.

While these moments of shattering the fourth wall met with mixed reactions from the spectators, the aspect that seemed to make the most sense to all the audiences was the play’s exodus, which we represented as a “second line,”20 a riotous “parade after the parade” composed of those who dance behind the “first line” of musicians, floats, and official marchers. Here, at the close of the play, the second line exodus acted as the reification of the moral ambiguity of the redistribution of wealth. Second lines are not exclusively celebratory revelries; they are also used to mark the end of certain portions of funeral rites (e.g., the sealing of the tomb and the departure of the hearse). As such, a second line is a ritual that is interchangeable and permeable; its form and action are the same whether the dance occurs at a wedding or a funeral, and it serves as an opportunity for people to join in the celebration or memorial service spontaneously.

In representing elements of Mardi Gras onstage and in tapping into the multivalent nature of these celebrations, our Wealth also aimed to play upon the ambiguity created by masking. To be sure, masks play different roles in theater and in a parade setting. For actors, the mask may serve to change their identity, but for the riders on the float or the spectators in the parade crowd, the masks disguise their identity. The resulting anonymity can be a license to engage in behaviors that are unexpected and even antisocial. In fact, the problem of masked participants acting out during Mardi Gras has plagued New Orleans throughout its history, and masks have been periodically banned from the parades and other celebrations. For example, in the 17th century, masked spectators were in the habit of throwing flour, often laced with lime, at other spectators; sometimes they threw bricks instead.21 Many traditional Mardi Gras activities enacted by masked “social clubs” are transgressive and would merit police involvement in a different context; at dawn on Mardi Gras day, the North Side Skull and Bones Gang, dressed in skeleton suits and masks, makes its way through select neighborhoods, pounding on doors with large animal bones until the homeowners answer.22 In Gheens, a small town in rural southeastern Louisiana, the locals preserve the tradition of courirs de Mardi Gras (Mardi Gras runs), in which masked and costumed men chase and “whip” spectators, and in particular the children in the crowd.23

It is this nature of the mask and the transgressive behavior it can encourage that we hoped to exploit in the instances of masking used in Wealth. In the later scenes of the play, as the characters experienced a greater and greater level of personal enrichment, they were given the opportunity to humiliate those who had previously been wealthy. Likewise, their wardrobe and makeup began to change, moving from their former worn-out clothes to the masks and costuming unambiguously associated with Mardi Gras, resulting in the concealment of their former identities as the working poor and underscoring their sense of entitlement in taking on the role of the oppressors. At the end of the play, as the characters moved to install Wealth in the agora as their new patron deity, the goddess herself reappeared briefly, her former beneficence likewise hidden by a mask as she demanded worship from the very people who had rescued her at the outset of the play. At the close, the full cast, many unrecognizable in their masks, danced off stage in a second line that was meant to play upon both possible interpretations for the activity as either celebration or mourning ritual.

Staging a Society on the Brink

Although the Wealth is unquestionably a comedy, the play’s commentary on economic disparity and the inversion of merit and reward is quite serious. For our production of Wealth, we signaled through the promotional artwork, the stage properties, and even the pacing of the production that, although the subject of the play was serious, the treatment it received would be satirical, critical, and comedic. Moreover, we wanted to emphasize not only the connection between ancient and modern, but also the cyclical nature of exploitation as both the oppressed and the oppressors switched roles.

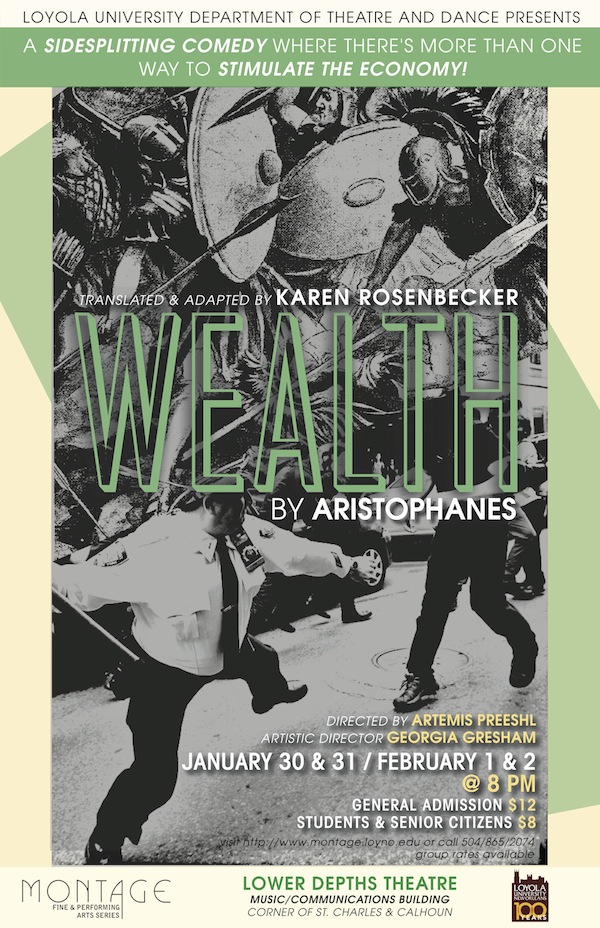

To this end, within the promotional artwork, the graphic designer juxtaposed ancient and modern images in order to emphasize the blending of the two time periods, and to suggest the progressive values highlighted in the adaptation and the subsequent parodies of them. In the poster, playbill, and program, we made the conscious decision not to use an image tied specifically to either Mardi Gras or to suffering in New Orleans (e.g., no images of destroyed houses or floodwaters) because a poster featuring either of those images would have created an expectation not only of the overall subject of the play but also the style of dramatic treatment. Moreover, John Biguenet’s Pulitzer Prize-nominated Rising Water trilogy, which intimately examines the lives of New Orleanians during and after Katrina, had just finished a local production, and Biguenet is also a faculty member at Loyola New Orleans where we would be staging Wealth.24 Given these considerations, we felt the promotional artwork needed to speak to the thematic issues at the core of Wealth, specifically questions of economic disparity and citizen action. Using elements drawn from both ancient and modern images, award-winning Loyola alumna Rachel Guillot created a master playbill that not only spoke to social unrest, but also helped to contextualize its cause and hint at the humorous treatment of the subject. The master image for the playbill features a grayscale image of Greek hoplites engaged in a disorganized scrum that elides into a black-and-white photograph of a police officer preparing to strike a protestor at an Occupy Wall Street demonstration.25 The officer’s portliness and exaggerated posture suggest the bungling of the Keystone Cops rather than effective law enforcement, while his ineptitude echoes the jumble of warriors above. The transition between images is covered by the play’s title, Wealth, in capital letters that are outlined in the green of U.S. banknotes.

It was in the set and stage properties that the creative team decided to foreground the New Orleans location for Wealth through a setting that suggested a combination of local devastation along with the ongoing depredations of Wall Street. For the first half of the play, before Wealth regains her sight, the garbage-cluttered stage was dominated by a blue tarp, a sight famous throughout the Gulf South as the marker of a home damaged by storms.26 Before the shroud of the tarp was a set of steps designed to recall local artist Dawn DeDeaux’s sculptural installations “STePs HoMe.” “STePs HoMe” debuted in 2008 at Prospect.1, an international exhibit of contemporary art, featuring exhibits and installations across the New Orleans metro area, including several in the ruins of the 9th Ward neighborhood.27 The “STePs HoMe” installations referenced the loss of homes in the damaging floods causes by levee breaches during Hurricane Katrina; each installation is composed of multiple sets of tombstone-like front steps that mark where houses once stood, thereby implying the loss of much more than the physical structure of the building.28 One of the “STePs HoMe” groupings was installed on Loyola’s campus for the duration of the Prospect.1 exhibit, and photographs of the installation, along with an annotated text, hung for years afterwards in Loyola’s Monroe Library, making the piece known to the Loyola community of faculty, staff, and students.

Although this initial tableau was a deliberately local and somber visual, when the house beneath the tarp and behind the sepulchral steps was “restored” by Wealth, the tarp was removed to reveal not the expected iconic New Orleans shotgun home,29 but a temple that owed more to the façade of the New York Stock exchange than to the Parthenon. The title “Wealth” was engraved upon the temple’s pediment, and as the enrichment of the onstage world progressed, the temple was often lit with a cascade of flashing, multicolored lights, like those of a slot machine hitting a jackpot. As a further visual to satirize the house’s function as temple of Wealth, the “throne” of the goddess was represented as a glittering, golden toilet, a prop meant to reference both the ubiquitous scatological humor in Wealth and the modern association of money with feces.30

While we aimed for the conflation of local and national with the stage properties, what we hoped to convey with the pacing of the production was the rapid, topsy-turvy change that the world on the stage was experiencing, as those who had been poor suddenly became wealthy, and vice versa. This breakneck pacing was meant to highlight the morally ambiguous actions and attitudes of the suddenly rich, and to set in high relief the uncomfortable proposition that perhaps the only difference between the virtuous poor and the decadent rich was, in fact, the amount of wealth they possessed, and that those who were enriched would find themselves becoming the people they had so reviled.31 We felt that this irony was accentuated by the incomplete and fragmentary nature of Aristophanes’ text, and decided to further emphasize those qualities in the staging of Wealth by creating a manic pacing evocative of “lemmings rushing to their deaths.”32 With this idea in mind, we compressed the action of the play—paring down the introduction of Wealth and the agon with Poverty in particular—to a 70-minute running time with no intermission. The resulting effect for both characters and audience was the creation of a society that, although experiencing rapid change, would nonetheless repeat the same cycle of exploitation and abuse.

From Men and Poverty to Women and Poverty

Integral to the thematic program of illuminating modern concerns by repurposing the ancient was our decision to “gender swap” many of the characters in this adaptation.33 We felt this was a fundamental step in that it allowed a point of access into a series of current discussions about the particular relationship of women and poverty in the twenty-first century. Fourth-century Athens maintained legal and social practices created to bar women from civic involvement and enfranchisement beyond their roles in religious rites and institutions; the public face of ancient Greek poverty would unquestionably have been a man’s. But, in post-millennium America, it is a woman’s. In each category of race and ethnicity, the majority of those living below the federal poverty level are women.34 Recent national events, such as the passing of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in 2009 and the issues of workplace discrimination highlighted by the “War on Women” during the 2012 presidential and congressional campaign season, brought these concerns to the fore on a national level.35 For New Orleans in particular, there is ample documentation that women, especially women of color, continue to bear a disproportionate amount of economic hardship in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.36

In Wealth, we focused on using the predominance of female characters to speak primarily to modern workplace inequalities and pay discrimination, specifically through the appearance and dialogue of the chorus, whom we reimagined as women trapped in poverty by the demands and vicissitudes of their minimum-wage jobs. Like Aristophanes’ chorus of farmers in Wealth, the Working Girls of Wealth bemoan their poverty, but unlike their ancient counterparts, they do so through language that is focused on their employment or lack thereof.37 Along these same lines of swapping gender to highlight economic disparity, we reversed the genders of the play’s two allegorical deities. The god Wealth became the goddess Wealth; in this case, the shift in gender adds to Wealth’s account of her exploitation at the hands of gods and men that begins the play. That Poverty (Peinia) was female in Aristophanes’ Wealth is not surprising in that the ancient Greeks conceptualized most monsters as female (e.g. Scylla, Charybdis, the Furies). In the original, her gender is a reflection of her powerful and malevolent nature, but in our Wealth we wanted to tap into modern perceptions as to who controls the nation’s economy; in light of this consideration, Poverty became a white man in a business suit whose dialogue was peppered with references to economic theory (e.g., Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand, Thomas Friedman’s Flat World, the ideal of trickle-down economics) and who consistently patronized the female characters.

In recasting the three lead characters in Wealth (Chremylus, Cario, and Blepsidemus) as women, we were able to create names that kept the connotations of the original Greek but also followed the program of enriching their dialogue with references to their economic plight. The old farmer Chremylus (Mr. Needy) became “Inida” (pronounced “I need a”), who is sometimes given the nickname “Needy” by her friends. Whereas Chremylus spoke of his poverty in terms of his moral merit (i.e., he was a good man who deserved to be rich), through Inida’s dialogue with other characters we revealed that she makes do by enmeshing herself in “off the books” economy of rent parties and plate sales, two means of raising money common in New Orleans’s black community and across the Gulf South in general.38 Cario in the Greek Wealth is a slave whose name is itself a synonym for “slave”; we renamed the character “Carry” as an aural pun on the woman’s name but also as an allusion to the action that the spelling implies; at one point the character is forced to bear Wealth on her back as she moves about the stage, literally and symbolically transferring the goddess and all she represents from one place to another. Chremylus’ nosy neighbor Blepsidemus, whose name in Wealth indicates his over-reliance on the city government, was recast in Wealth as “Faith.” As her name implies, the character is easily duped by authority figures, Poverty in particular, but whereas Blepsidemus’ ultimate rejection of Poverty rests on his desire to feast rather than fast, Faith’s decision stemmed from the revelation that, in Poverty’s economy, women make less pay for equal work.

“Twice-Turned” Costuming and Mardi Gras Glitter

To further this play between poverty and social upheaval, we worked with costume director Kellie Grengs to create a wardrobe of garments appropriated from other productions or purchased at local thrift stores, and then reconstructed and repurposed them for the production. Although we did feature some elements of Greco-Roman costuming in order to continue our program of mixing ancient with modern, we hoped the modern costumes could convey a different message. During the planning of the wardrobe, we spoke of creating a “twice-turned” aesthetic as a visual signifier for the endemic lack of resources that we wanted to project. The phrase “turning a garment” describes the process of deconstructing a worn piece of clothing in order to reassemble it with the fresher, cleaner “inside” face of the fabric now turned to the outside; a “twice-turned” garment is one that has been put through this process yet again.39 For those of us involved in the production, this decision to use a second-hand wardrobe was also a conscious commentary on the shrinking budgets of most theater programs. For our audience of nontheatrical outsiders, we hoped the hand-me-down, hodgepodge effect of the wardrobe would prompt reflection on the lack of resources and the division between classes (e.g., rich and poor, human and god, elite and subaltern), as well as making them sensitive to the shift to flashier clothing and then to Mardi Gras costumes as wealth is redistributed.

In particular, the use of modern “uniforms” for some characters allowed for a secondary level of social commentary. For example, the gown worn by Just Citizen evoked both a judge’s robes and a college student’s graduation regalia, thereby playing up the civic responsibility and financial obligations of each role respectively. The uniforms of the Working Girls, evocative of big-box stores and fast-food chains, marked them as distinctly outside the economic “safety” of the middle class. The superhero costume worn by the Priest of Zeus alluded to the status he should receive as the god’s earthly proxy and further mocked his inability to derail the redistribution of wealth.

The shifts in costuming for the three lead characters (Inida, Carry, Faith) and the Working Girls, done as their enrichment occurs, acted as a visual cue to match their shifting attitudes about poverty and the poor. In particular, Carry’s move from dingy garments to sequined dress also marked her “devolution” from crusader against poverty to someone who had no qualms in saying, “Who knew poor people could be so annoying?”40 The Working Girls displayed the greatest shift in their costuming, indicating the most pronounced shift in fortune and attitude; the trio ended the play costumed for a Mardi Gras parade, their identity hidden behind half-masks, cotton-candy-colored wigs, feather boas, and party-colored dresses. Their attitudes likewise changed from railing against the indignities forced upon them by their jobs to mocking those who come to Inida’s house for help, and finally to giving themselves completely to the madcap worship of Wealth that closes the play.

Vase Paintings and Modern Vernacular: Blocking and Dialogue

In adapting Aristophanes’ play, we sought to further the blend of ancient and modern through onstage movements and certain facets of the dialogue. For example, the blocking of the onstage movements shifted between stylized poses drawn from Greco-Roman vase paintings and sculpture, and unaffected, informal gestures, like characters hugging each other or high-fiving. In some scenes, the styles were juxtaposed, as during the agon when Inida and Poverty were initially held in an exaggerated tableau while Faith meandered about, inspecting the various charts Poverty had set up.

In the dialogue, we tried to convey the mixture of sacred and profane, lofty and louche, universal and local that characterizes the Aristophanic original. In one particular scene—Carry’s description of Asclepius healing a disguised Wealth—the adaptation of the dialogue employed a similar alternation between the moment of Asclepius’ revelation and the offhand and dismissive reactions of Carry and Faith. To further create this quick pivot in tone in our production of Wealth, one actor served as a mask for another:

(Carry positions herself behind Faith; the audience sees Faith’s lips move, but hears the deep voice of the god Asclepius. Faith stands still as a statue; her eyes are wide but her face is expressionless, like a blank mask.)

Carry: (in a deep, solemn voice) Neoclides, in return for your faith, I restore the light to your eye.

(Both actors step apart and shake themselves out, as if recovering from a moment of divine possession.)

Faith: So he (Asclepius) didn’t know it was a woman?

Carry: No, you know HMO’s only let doctors see you for like ten minutes now. He didn’t have time.41

Here, in Wealth, the humor of the exchange rests upon the juxtaposition of the holy moment of the god’s appearance with Cario’s gross breach of decorum, all of which is highlighted by the fact that he is recounting the moment to a woman (Chremylus’ wife).

Wife: But didn’t the god come to you?

Cario: Not yet, but he did just after that. While he was approaching, I did

something really funny; I let off a ginormous fart. I’d gotten bloated from

porridge, you see.

Wife: I bet that made him want to get close to you!

Cario: No, but it offended his attendants. Iaso blushed and Panacea held her nose.

My farts don’t smell like incense, you know.

Wife: But what about the god himself?

Cario: It didn’t seem to bother him, by Zeus.

Wife: This is a pretty crass kind of god you’re talking about, then.

Cario: No, he’s a doctor. They’re used to eating shit.42

In addition, Aristophanes’ consistent references to other authors and poets were adapted and updated by lacing the dialogue of Wealth with references to modern authors, as well as pop music and pop culture. Sometimes these were brief (Inida mentioned Tumblr, Carry invoked Orwell’s “some animals are more equal than others”), but sometimes these allusions were longer and drawn out more explicitly for the audience, like this scene between Inida and Poverty in the agon; here, Aristophanes’ reference to lyric verses was recast as a familiar quote from A Christmas Carol.

Poverty: There can’t be a place of peace and plenty without there also being a place of conflict and deprivation. Some have to suffer so that others can prosper.

Inida: Ah, I see. So it’s down to “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”

Poverty: Don’t you put your Dickens in my mouth! He was writing about abject beggary and a complete lack of resources. I’m talking about the natural fluctuations of the market.43

In the original, at this juncture in the agon, the joke hinges on Chremylus’ recasting of verses written by the lyric poet, Alcaeus, in which Poverty and Helplessness are said to be siblings.

Chremylus: (sarcasm) I am demonstrating how you are the cause of oh-so-many

blessings, aren’t I?

Poverty: You are not talking about my way of life at all! What you are talking

about is the way of life suffered by those who are destitute!

Chremylus: Well, hasn’t it been said that Destitution is the sister of Poverty?44

Within our adaptation, in order to reflect Aristophanes’ firm grounding in Athens, we decided to frame Athens qua New Orleans by keeping a select few of those original references (e.g., Inida consults Delphi at the start of the play, rather than, say, the spirit of Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau), but then to shift the majority of them to terminology familiar in the New Orleans vernacular. For example, Faith and Inida described their initial state of poverty in terms of “plate sales” and “rent parties,” two traditional means of raising money familiar in New Orleans.45 Later, when Carry taunted Hermes with a litany of choice foods, Aristophanes’ catalogue, which stressed the god’s lack of resources,46 was transformed into a list of classic New Orleans eateries and dishes, emphasizing the local preoccupation with food, as well as the ongoing enrichment of the house.

Hermes: Please, baby, come on, please just let me inside to get something to eat. It…it smells like you’ve got barbeque in there.

Carry: Yep.

Hermes: (sniffing) And…and…shrimp on the grill.

Carry: We’ve got it all: butterfly catfish from Mittendorf’s, sweet baby backribs from Rocky and Carlo’s, onion rings from College Inn, oyster po-boys from Guy’s, barbeque shrimps from Pascal’s…

Hermes: Anything from Coquette?

Carry: Just their salt shaker.

Hermes: About time someone took that away. But I’m ravenous for the rest!47

Results of the Production—Impact on the Audience

When we began adapting the play into what became our production of Wealth, we knew we had a unique opportunity to observe how our student cast, crew, and audience would react to encountering ancient comedy on the stage rather than on the page. A series of talk-back sessions, in-class visits, and a brief survey all provided us with a sense of the results of our production choices. In particular, we were eager to hear the students’ take on three things: the link between New Orleans and ancient Athens, the impact of enacting a portion of Mardi Gras onstage while Mardi Gras was being held city wide, and the audience’s interpretation of the overall “message” of the play. What we gleaned from these sessions suggested some specific things to us about our students’ experiences with theater, and specifically with Greek drama.

It is perhaps not surprising that the reactions and perspectives of the student cast and crew differed from those of the students in the audience. Because they spent more time with the script and had background information provided by the dramaturge, director, and writer, the cast and crew had a better grasp of the parallels between the poverty of fourth-century Greece, which formed the backdrop for the original, and the disasters that had crippled New Orleans, which formed the backdrop for our adaptation. Moreover, many of them understood that the New Orleans on the stage could be seen as a “stand in” for many cities in the U.S. (e.g., Detroit, Stockton, Oakland), or even for modern Athens. Although the actors initially wondered how to interpret their characters’ shifting fortunes (i.e., was it a good thing that they were suddenly rich?), they embraced the ambiguity the ending implied, seeing it as both a celebration of a new way of life and a requiem for a former one.

However, our actors did have trouble connecting with the audience through the level of metatheater we envisioned. Although our Wealth was not conceived as an original-practices production (i.e., no masks, reduced choral element, modern dress), the actors were asked to engage in the presentational style of acting characteristic of Aristophanes’ stage. On this particular point, theater practice illuminated an issue that work with the text could not: the actors, for all their dedication and skill, were unaccustomed to breaking the fourth wall and speaking their lines to the audience, rather than to the other characters. Although the actors did acclimate their onstage movements and points of eye contact in order to treat the audience as, in effect, another cast member, these were techniques that many of them adopted throughout the show’s run, growing more comfortable and confident in interacting with the audience with each performance and with greater effect each time. For our student cast and crew, then, the challenges of our production choices were felt most keenly in the area of theater practice, rather than interpretation, as we encouraged them to embrace a style of acting that was largely unfamiliar and counterintuitive.

However, when we spoke with our student audience in talk-back sessions and via a brief survey, we found that the audience had a different set of concerns regarding the production choices we made. What emerged initially in these sessions was that our audience, almost unanimously, had appreciated the conflation of impoverished ancient Athens and post-Katrina New Orleans, but that for many the lack of background knowledge for Old Comedy profoundly affected their viewing experience. Many of the students came to Wealth with no background in theater, let alone Greek drama. Those students who had studied Greek theatre had some background for tragedy and were familiar with tropes such as “the fatal flaw of hubris” and the ideal of catharsis. Likewise, their experience of Greek drama came from watching, usually in a video format, a more traditional treatment of, for example, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. Students were largely unfamiliar with any Greek comedy except Lysistrata, and only a few had seen clips or stills from a production of any comedy. Although we did not speak with or survey all the students who attended the play, the information we did receive allows us to conclude that few had ever read a Greek comedy and that none had seen a Greek comedy onstage before seeing Wealth.

This lack of context for what to expect from a Greek comedy versus, for example, a traditional production of Greek tragedy, drove the majority of the discussion in the talk-back sessions. In a revelation that we found surprising, the student audience expressed trouble contextualizing the pervasive metatheater of the play, as well as concern about the ongoing stream of insults the characters exchanged. In terms of interaction between actors and audience, survey respondents expressed surprise at the direct address of the acting style, and several students said that they did not know whether they should acknowledge or respond to the actors who appealed to the audience. Others noted that their previous visits to the theater in a scholastic setting (usually as part of a high-school field trip) had come with the admonition that they were to sit still and be quiet at all times. Many students came with the expectation that the decorum of a traditionalist production of Macbeth, for example, was typical for all live theater. For students with this background in attending theater, the obscene and aggressive nature of the humor in Greek comedy came as a shock, and one student worried that “some jokes sometimes alienated the audience.” It was the entrance of the Old Cougar [Old Woman], a female character played by a male actor in our production, that gave one group in particular a sense that the audience was welcome to participate and laugh aloud at the aggressive teasing some characters experienced. In this case, the audience made the connection to pop-culture figures, such as Tyler Perry’s Madea, for whom the element of drag entails the use of bawdy language, physical comedy, and a running social commentary. The audience also participated spontaneously and actively when the second line began at the close of the play; the culture of “second lining” is so strongly established in New Orleans that upon the musical cue of “Do Whatcha Wanna” by the Rebirth Brass Band,48 the audience began clapping in time with the familiar song, even over the play’s last line of dialogue, and even without knowing what sort of closure the dance provided.

For many students, the lack of traditional arcs of character and plot development was frustrating. One student’s concern that “the bad guy (i.e., Poverty) did not get punished enough for his bad behavior” seemed to reflect an expectation, created by modern drama and sitcoms, that characters bear the consequences of their bad behavior. Still others seemed to come to the play expecting Greek comedy to be similar to Greek tragedy in terms of character growth and the resolution of moral dilemmas, with one student offering, “The adaptation/the script was rather simplistic and it left very little room for character development. With this, the play lacked depth and it was difficult to be engaged as an audience member.” Another student pointed directly to the fact that the audience was puzzled by the unique form of Old Comedy, saying “I appreciate the attempt at honoring Greek tradition, but it was lost on this audience.” Despite the difficulties in understanding some of the generic facets of Old Comedy that we embraced in adapting Wealth, the students were able to synthesize the production’s relevance to issues in post-Katrina New Orleans, Post-Great Recession America, and even modern Greece. This level of engagement between theater and society was something we very much hoped to bring across in Wealth. It was gratifying to have the students respond positively to the fact that comic theater could engage in political discourse. An overwhelming majority of the students perceived the irony in the play’s suggestion that “the more things change, the more they remain the same” (this was one of the survey questions, and a point raised in talk-back sessions).49 One student reflected on this particularly in light of the parallels between ancient Athens and modern New Orleans, writing, “I really enjoyed the juxtaposition of present versus ancient circumstance.” Most appreciated the link between the production and Mardi Gras (one wrote, “It was fun to see the Mardi Gras aspect and audience interaction”), but it was hard even in discussion to get a sense whether the students in the audience understood the ambiguity we hoped to suggest in representing the exodus as a second line. Although many appreciated the familiar rhythm and spectacle, no student indicated without prompting that the close of the play could be seen as both celebration and funeral, as the beginning of the new world and the end of the old, and as a foreshadowing that perhaps the characters’ access to wealth would be transitory.

Our encouraging overall conclusion from conversations with our student cast, crew, and audience was that although many of them were unaware of the conventions of Greek comedy, they were still able to “get what the play meant,” as one student put it. Certainly staging Wealth during a semester in which courses highlighting Greek drama were offered would have created more opportunities for all students involved to become more familiar with the genre and perhaps also expand the ways in which they connected with and interpreted the play. But we do believe the students’ appreciation of the setting and message of Wealth says something quite positive about the validity of our production choices, and about the power of theater to reimagine and represent events in order to speak across space, time, and cultural norms. It also suggests that students are engaged by and receptive to works of theater beyond familiar and canonical plays, and that with a modicum of introduction, they are willing and able to appreciate works from challenging genres. On a more general level, our work in translating, adapting, and performing Wealth has demonstrated to us that the play is eminently accessible to modern audiences. Its wry look at socio-economic reform feels familiar when staged before an audience who themselves are caught in a struggling economy. The ability of directors and translators to infuse adaptations of Wealth with more pointed or particular economic and social criticism—as we did—makes the play an excellent fit for skewering the fitful and fickle modern financial market and those who dream of being its master. We are thrilled to have been part of a resurgence in theatrical interest in Wealth, and we hope to see the play claim a place on the modern stage beside Frogs and Lysistrata.50

Appendix I: Cast of Characters

Comparison of List of Characters in Aristophanes’ Wealth and Rosenbecker’s Aristophanes’ Wealth; Gender of each character is indicated by (m) or (f).

Aristophanes Rosenbecker Cario (m) Carry (f) Chremylus (m) Inida (f) Wealth (m) Wealth (f) Chorus of Farmers (m) Working Girls (f) Blepsidemus (m) Faith (f) Poverty (Penia) (f) Poverty (m) Chremylus’ Wife (f) n/a Just Man (m) Just Citizen (f) Informer (m) Mortgage Broker (m) Old Woman (f) Old Cougar (f) Young Man (m) Boy Toy (m) Hermes (m) Hermes (m) Priest of Zeus (m) Priest of Zeus (m)

Appendix II: Full Program

The original program has detailed information about the production. It will open in a new window.

notes

1 Rosenbecker, Karen. “Wealth.” Script, © 2013, p. 3. For the original sentiments, see Ar. Plut. 26–39.

2 Perhaps the best-known example of this is Paul Chan’s 2007 staging of Becket’s Waiting for Godot in the Lower Ninth Ward and in Gentilly, two New Orleans neighborhoods hard hit by flood damage in Katrina. Chan’s decision to stage the play outdoors, using abandoned houses and debris as scenic backdrops, tapped into what he called “the terrible symmetry between the reality of New Orleans post-Katrina and the essence of this play, which expresses in stark eloquence the cruel and funny things people do while they wait: for help, for food, for tomorrow.” (See Chan’s introduction to the project at www.creativetime.org/programs/archive/2007/chan/welcome.html and discussion of the productions at www.nytimes.com/2007/12/02/arts/design/02cott.html?pagewanted=all).

3 Aristophanes’ heroes often run up against characters who are drawn directly from the Athenian social/political milieu and serve as antagonists or comic foils (e.g., Cleon in Knights and Wasps; Socrates in Clouds; Euripides in Acharnians, Women at the Thesmophoria, and Frogs). In addition, problems created by the protracted nature of the Peloponnesian War (e.g., the Spartan depredations of Attic farmlands in Acharnians, the diminishment of civic festivals in Peace, the sexual dysfunction in Lysistrata) are frequently the reason for the hero’s actions.

4 Specifically in this play, the involvement of the pan-Hellenic oracle at Delphi and the frequent mentions of Zeus Soter, whose cult was enjoying a surge of popularity across Greece (see Parker, Athenian Religion [Oxford, 1996]), suggest an Athens that could be any other polis. Also, references to specific Athenians are minimal and brief (cf. 174–180, 303–306, 550, 602).

5 For background on the endemic poverty in Athens and fourth-century Greece, see Strauss’ Athens after the Peloponnesian War: Class, Faction and Policy 403–386 B.C. (Ithaca, 1987) and David’s Aristophanes and Athenian Society of the Early Fourth Century B.C. (Leiden, 1984).

6 For a description of the Argos riot, see Diodorus Siculus XV.57–58.

7 See Lysias 22.1–12.

8 See Rhodes, The Athenian Boule (Oxford University Press, 1985).

9 The continually updated “Latest News” section illustrates the longevity of the movement (www.occupywallst.org).

10 A brief discussion of the transfer of wealth in the decades since the end of World War II and a comparison between the distribution of wealth circa 2013 and the distribution of wealth circa 1928 is available at www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/12/05/u-s-income-inequality-on-rise-for-decades-is-now-highest-since-1928/. While the comments to the post are anecdotal, the anger, fear, and contempt expressed in them represent an illuminating cross-section of public sentiment on the subject.

11 For an overview of this series of shootings, see www.huffingtonpost.com/mobileweb/2013/05/12/mothers-day-parade-shooting-new-orleans_n_3263539.html.

12 See www.nytimes.com/2014/07/10/us/ray-nagin-former-new-orleans-mayor.html?referrer=&_r=0.

13 See Kocha’s editorial for a discussion of that label for the city in light of recent events (www.thedailybest.com.2012/11/09/the-city-that-care-forgot.html).

14 See note 2.

15 Cartledge in his essay “Deep Plays: Theater as Civic Process in Athens” suggests that the City Dionysia, in its mid-fifth-century form, was a reflection of the highly political and competitive nature of public life in Athens, and that the drama on the stage was a mimesis of the drama in the Athenian assembly and law-courts (The Cambridge Guide to Greek Tragedy [Cambridge University Press, 1997]).

16 K. J. Dover refers to this behavior as “self-assertion,” a manner of comportment which characterizes all Aristophanes’ heroes and many of the characters allied with them (Aristophanic Comedy [University of California Press, 1972]).

17 See an excerpt from that speech and Nagin’s subsequent explanation of the comment at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QEH9u26Vlhk.

18 See www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/compress/2006/504/03.htm.

19 See www.asergeev.com/pictures/archives/compress/2006/502/13.htm.

20 For a general discussion of second lines, see http://www.frenchquarter.com/history/SecondLine.php. For their ubiquity in New Orleans culture, see the ever-changing list of scheduled second lines at www.wwoz/new-orleans-community/inthestreet.

21 For more on this topic, see James Gill’s The Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), specifically pp. 35–51.

22 Much of the early history of the various “tribes” has not been preserved (“Forward,” Mardi Gras Indians, Smith and Grovenar [Pelican Press 1994]), but the post-Katrina activities of the North Side Skull and Bones Gang have been chronicled by the Times-Picayune (Litwin, “Skull and Bones channels the spirit of Mardi Gras” [http://www.nola.com/nolavie/index.ssf/2012/02/skull_and_bones_gang_channels.html]). Many video clips of the Skull and Bones Gang making their rounds may be found on YouTube, but the following video provides a series of historical images as well as footage of modern “bones men” knocking on doors on Mardi Gras Day and yelling their traditional warning of “you gotta get your life together!” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eRj7oeXyoqI).

23 The courirs de Mardi Gras are still run in small communities in rural southeastern Louisiana (Gheens, Mamou, Iota, and others). The unique traditions of the chases, including both the pursuit of children and their various parade elements, have been described in magazines on tourism and travel (Bass, “Courir du Mardi Gras,” Deep South Magazine. 14 February 2011) and analyzed by academics (Lindal, “Bakhtin’s Carnival Laughter and the Cajun Country Mardi Gras,” Folklore 107). Although the video is not of the highest resolution, perhaps the best example of the transgressive behavior allowed during the chase is the following brief clip: the footage clearly shows a grown man, whose identity is hidden by a mask and colorful clothes, aggressively chase and tackle a child before “whipping” the boy with a fabric lash, all as amused adults look on and cheer the pursuer (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3a1pzuQzTpA).

24 See www.bigeunet.com/plays.

25 View full program in Appendix II.

26 To get an idea of the ubiquity of blue tarps in the Gulf South, see the photo of the houses on the cul-de-sac that appears on the homepage for the Hurricane Management Group (www.hurricanemanagementgroup.com/blue-roof-leak-plastic-tarp/). For background on the use of the tarps and the ironic message they send, see FEMA’s “Blue Roof Program” (www.fema.gove/newsrelease/2004/10/2/operation-blue-roof) and also comments on the program’s effectiveness (http://www.pogo.org/our-work/reports/2006/co-kc-20060828.html).

27 For an overview of Prospect.1, see http://www.prospectneworleans.org/past-prospects-p1/.

28 For background on and visuals of the installation, see www.dawndedeaux.com/steps1.php.

29 See photos at http://www.nola.com/homegarden/index.ssf/2014/02/shotgun_geography_new_orleans.html.

30 Freud argues that the child’s mind links feces to money, gold in particular, and thence connects money with anal eroticism (On Transformation of Instincts as Exemplified in Anal Eroticism [The Penguin Freud Library (vol. 7), 1991]). For the evolution of the connection across twentieth-century psychoanalytic literature, see Trachtmans’ “The Money Taboo” (http://www.richardtrachtman.com/pdf/moneytaboo.pdf).

31 In fact, the majority of students surveyed felt that the overall message of the play was “the more things change, the more they remain the same.”

32 Translator and adapter Rosenbecker felt this sense of unseen, impending doom was so central to Wealth that she toyed with making this phrase a subtitle (i.e., Wealth or Lemmings Rushing to their Deaths).

33 See Appendix II for a side-by-side comparison of characters’ names and genders in the original and adaptation.

34 For statistical information, see the statement on women and poverty issued by the Center for American Progress (www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/report/2008/10/08/5103/the-straight-facts-on-women-in-poverty/).

35 The term “War on Women” was used widely during the 2012 campaign season to refer specifically to the perceived assault on women’s rights resulting from certain Republican Party policies (www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/05/12/war-on-women-2012_n_1511785.html). Perhaps the best-known sound bite relating to workforce discrimination and pay equality was Mitt Romney’s “binders full of women” gaffe during the second presidential debate (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_LQ3eHSZ9c).

36 The Institute for Women’s Policy Research has compiled a 12-page overview of poverty in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast region in the wake Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma (www.iwpr.org). In addition, the meta site CivilRights.org maintains a list of papers, articles, and conference presentations that focus on the link between poverty and the effects of Hurricane Katrina, many of which speak to the uniquely vulnerable state of women (www.civilrights.org/poverty/katrina/).

37 For example, in Aristophanes the line “it is really possible for us to be wealthy?”(286) in our Wealth becomes “if what you’re saying is true/you mean we can really be rich/we don’t have to work like we do?” [Rosenbecker, p, 11].

38 The term “rent party” is perhaps most formally associated with its use during the Harlem Renaissance (www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/progress/prohib/rent.html). The origin of the term “plate sale” is more difficult to determine. Like bake sales, plate sales are a common fundraising tactic across the South; instead of baked goods, they feature meat dishes or even whole meals assembled and sold on individual plates.

39 The best illustration of this meaning and practice is Dickens’s description of Mrs. Cratchit at the family’s Christmas dinner “dressed out but poorly in a twice-turned gown” (“Stave Three: The Second of the Three Spirits,” A Christmas Carol).

40 Rosenbecker, p. 43.

41 Rosenbecker, p. 27.

42 Plut. 695–706. Here Aristophanes alludes to the practice among ancient physicians of tasting a patient’s urine and feces as a diagnostic technique.

43 Rosenbecker, p. 22.

44 Plut. 545–549.

45 See note 38.

46 In Wealth, This scene between Cario and Hermes also relies on a series of aural puns. For example, Hermes bemoans the ham (κῶλης) he used to receive from his worshipers, and Cario responds that he can “ham it up all he likes” (ἀσκωλίαζ’) but he is not getting any (1128–1129).

47 Rosenbecker, pp. 41–42. For the referenced passage in the original, see lines 1125–1133.

48 Full song available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-GiQFveaqHo.

49 See note 31.

50 This brief overview of the various productions and their timing suggests a growing awareness of the socioeconomic relevance of the play and its appeal to modern audiences. Wealth has received several recent productions, with most of them being staged in Greece. During Wall Street’s bear market of 1994, the National Theatre of Greece produced the show. As Greece suffered its own economic crises, Wealth enjoyed a sharp uptick in frequency of productions. In 2004, to spoof the “global recovery” from 9/11, the Medieval Moat Theatre in Rhodes staged Wealth. In 2010, Diagoras Chronopoulos, director of Karolos Koun Theatro Technis, remounted his 2000 production of the Ploutus to highlight socially inequitable distribution of wealth in Athens. In 2011, Yannis Rigas and Grigoris Karantinakis recomposed Ploutus in the National Theatre of Northern Greece’s production at the acoustically perfect Epidaurus. Here in the U.S., productions of Wealth are on the rise as well. The Curious Frog Theatre Company, based in Queens, presented Wealth (Profit) in 2009 (www.curiousfrog.org/archive.php); Magis Theater of New York presented an adaptation entitled Occupy Olympus in August 2013 (www.occupyolympus.com); the Classics Department at Boston University presented a staged reading, titled Wealth, in April 2013 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMaDp56J9m4).