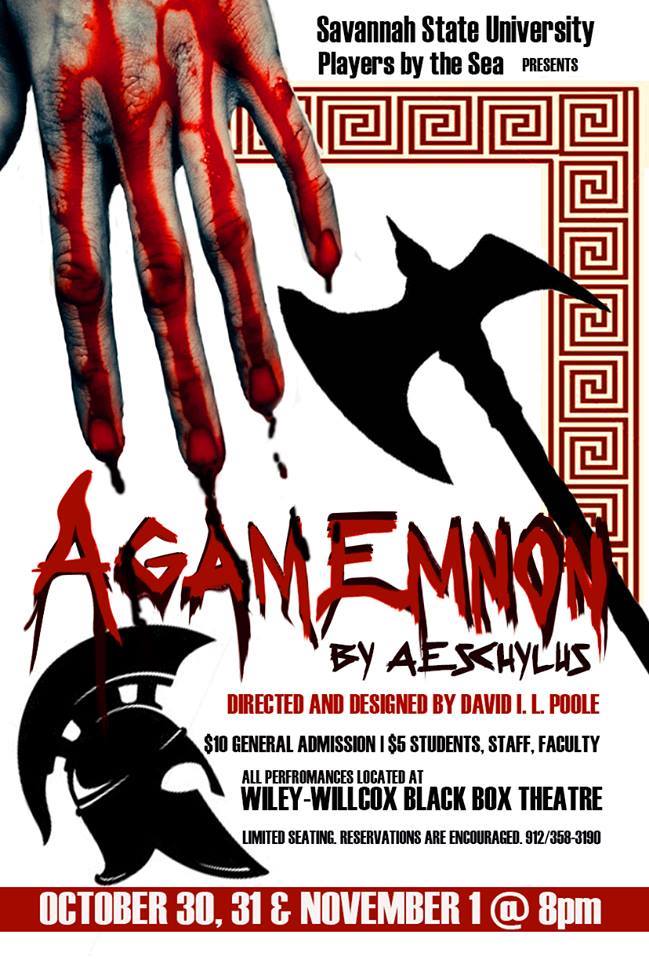

Agamemnon

Directed and Designed by David L. Poole

October 30-31 and November 1, 2014

The Wiley-Wilcox Black Box Theatre

Savannah State University

Reviewed by Ruth Scodel

The University of Michigan

Until I saw the poster for this production, I had never considered Agamemnon as a Halloween entertainment, but it has almost enough blood for a slasher movie and is a ghost story besides. Also, I would probably not have selected a tiny black box theater as the ideal venue, thinking of the vast spaces that the play evokes. But a small, dark theatre has advantages. Insofar as the chorus represents the city, the city itself seems an extension of the house. While I found Cassandra was a little overplayed when she threw herself against the walls, in memory the effect feels right—she is trapped, and the audience experiences some of that same claustrophobia.

The chorus, though, was not a straightforward group of Argive elders. They were masked—the rest of the cast were not. The masks were convenient, enabling the chorus members to take other roles. The masking was especially effective when, during the parodos, one chorus member removed his mask and became Calchas—the switch broke up the long narrative and powerfully conveyed the slippage between past and present. These masks, though, also made the chorus uncanny: they were not flexible or naturalistic, but were hard and distinctly creepy, with long beards. Sometimes the chorus members were a group of Argive elders, especially in their final confrontation with Aegisthus, but sometimes something else, hard to define: spirits of the lingering past, perhaps, or articulate zombies.

This production had a mostly student cast, and Savannah State University is a historically black institution. It does not offer Greek or Latin, it is not a wealthy college, and 90% of its students receive financial aid. Yet Aeschylus was hard to understand even for audiences in the late fifth century BCE, and for a modern audience—people who don't know the history of the Pelopids, the system of Greek ornithomancy, or the problems of theodicy with which the choral songs grapple—he is harder still. Using Ted Hughes's adaptation helped; his version unpacks Aeschylus' dense language. I would never use his translation for teaching, because too often his elaborations distort. In the theatre, though, an audience cannot stop to puzzle through ambiguities, and Hughes's version conveys enough meaning and is real poetry. Cutting also helped, since this production omitted, for example, some choral song and the herald's account of the storm and Menelaus' disappearance. During the parodos, chorus members displayed the eagles on sticks along with the hare; it felt cheesy to me, but was probably helpful for audience members who didn't know the play. On the other hand, a few moments earlier, when they waved a piece of fabric to represent Aulis and the shadow of birds appeared through it, the effect was truly mysterious and numinous; the gods were communicating, but their message was predictably unsure.

This production was almost a lesson in how effective and useful stage resources can be, both those available to the ancients and those not. Agamemnon, wearing armor, entered on a single chariot, with Cassandra huddled in it and no other booty displayed. The oversized chariot by itself announced what the Agamemnon of this production was. In the carpet scene, I did not feel that this Agamemnon felt any real fear of offending the gods or exceeding human limits. He resisted because he would automatically resist Clytemnestra, and at the moment when he agreed that she had "won," he turned and violently kissed Cassandra before descending from the chariot, as if to declare that Clytemnestra's small victory was irrelevant. This bit of stage business was brilliantly shocking.

The main set had a short flight of stairs leading to the palace facade. The chorus was at the level of the front row of audience seating, while Clytemnestra could stand on the stage at the top of the stairs, above the chorus without being completely cut off from them. After the murders, though, the stairs were pushed to the side so that there was a narrow raised stage at house left with no direct access from the choral space. Clytemnestra came out standing over the corpses in a shallow, square basin—it was, in effect, an eccyclema. Aegisthus then spoke down to the chorus from the side stage, so that the staging reinforced his lack of involvement in the earlier action and his failure to engage the chorus. Aegisthus wore an orientalizing costume with a fez that made me think of a toy monkey with cymbals, an image that fits the character pretty well.

I have often wondered what could make Aeschylus' Clytemnestra, although she must need a male figurehead, accept this weakling. This production did not bring out quite sharply enough how his arrival interrupts her attempt to make a bargain with the evil spirit of the family—that she will take only a little of the wealth if it will leave the house in peace (1575–6). This is probably not a workable bargain anyway, but Aegisthus, who wants all the wealth and power, has no interest in it. However, seeing the play performed by an African-American cast gave this aspect a new resonance, one I have not yet been able to think through. Agamemnon is a miles gloriosus, though not at all an amusing version of the type, while Aegisthus is a nasty little tyrant, almost but not quite a complete puppet—he will let Clytemnestra mostly control him as long as he can push around others.

These are the men between whom Clytemnestra can choose, and seeing this production invited me to wonder what this matriarch could have been like if she had ever had a man worth having. The family curse expresses itself not just in her need for revenge, but in the men's greed for wealth and power. That greed is eternal, so that the play can work even without many of its great meditations on the causes of human ruin. The house is haunted, but the ghosts would not come out if we didn't invite them.