The Masked Chorus in Action—Staging Euripides' Bacchae

Chris Vervain

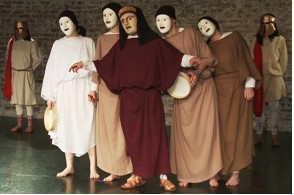

Figure 2: Pentheus' desires made visible

Figure 2: Pentheus' desires made visible | ||

Figure 1 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Figure 5 |

Figure 6 |

Figure 7 |

Figure 8 |

Figure 9 |

Figure 10 |

Introduction

The focus of this paper is the staging of the masked chorus in my 2010 production of Euripides' Bacchae in the Philip Vellacott translation. This production was designed for a proscenium-arch staging and created for film rather than live performance. I am a director of masked theatre, working with masks I have created myself. The conventions of modern masking that I follow emanate from Jacques Copeau and were transmitted, with further development, in a largely practice-based tradition by such directors as Michel Saint-Denis, Jacques Lecoq, and their followers. In this tradition, the mask is seen as a type of physical theatre, a form, that is, "that puts movement and action before voice and text."1 Meaning is constituted in particular ways: through gesture, the position and movement of the masked performer's body, its physical interaction with other performers' bodies, the pathways it and they take through space, and the stage pictures thus created.

Certain fifth-century Athenian vase paintings, in particular the “Boston Oresteia” (Figure 1), although not overtly theatrical, may reflect an influence from the theatre.2 To a practitioner of drama, these images suggest a variety of physical theatre in which enactment is almost dance-like (in the modern sense of the term “dance”). While it is not my intention to create the sort of dance theatre that I see in these paintings, I favour the idea of tragedy as a mobile form, rejecting Oliver Taplin’s vision of "long static scenes" with a chorus that would have "stood (knelt or sat) as still and inconspicuous as possible."3

As the modern tradition of mask emphasises the physical aspects of performance, I have had to adapt its conventions to do justice to the complex texts of the ancient plays. The visual nature of mask in drama, however, remains at the forefront. It is also my aim to convey clearly the action of the main episodes so that it is not obscured by an atmosphere of ritual "otherness". As Stephen Haliwell observes, a "widely credited and deeply entrenched supposition . . . that tragic masks were religious in origin" still holds sway in modern scholarship,4 a supposition that often leads to a ritualistic interpretation of the plays. The Bacchae in particular has been interpreted as reflecting Dionysiac mystery cult.5 When tragedy is interpreted as "ritualistic" drama, for example in Peter Hall's 1981 Oresteia, masks may be an important ingredient. Rush Rehm, reviewing this production, describes the "alliterative language, heavy rhythms, similarity in tone and mood, impersonal masks, the ritual pulse", all aimed to produce a hypnotic effect.6 Precisely to avoid such an effect, I employ the techniques of modern mask theatre in conjunction with the basic "w" questions usually associated with Stanislavski: who is doing what to whom, where, when, and why? In this way the thought processes, objectives, and interactions of the characters are plausible, but the fact of the masks rules out any idea that this is a variant of the theatre of naturalism.7

Although I have no intention of reconstructing ancient performance practices, I do assume that a consideration of the ancient theatre, or rather what we understand of it, can inform our practice today. The role and identity of fifth-century choruses has received considerable attention in the scholarly literature: whether they are to be interpreted as witnesses and mediators of the action for theatre audiences,8 as an "actor"9 with a fictive identity in the world of the play, as an active or purely passive entity, or as a ritual presence providing a deeper, philosophical and religious contextualisation of the action of the plays.10 The debate over whether Greek drama was predominantly an audial or visual experience11 is relevant in envisaging the degree and form of the chorus’ visible participation in the main episodes. These issues have informed my staging of the Bacchae chorus. In approaching the subject more from an applied than a theoretical perspective, I have found additional dramatic uses for the chorus. The technicalities of staging masks have revealed, moreover, that even an apparently simple matter such as employing the chorus as witness to the drama involves a choice in which the mask offers both opportunities and constraints.

Making Use of the Chorus

The chorus of the Bacchae are from Lydia and Phrygia, female followers of Dionysus who have travelled with the disguised god throughout various lands of Asia Minor before arriving with him in Thebes. In my production I refer to them merely as Maenads, avoiding the sort of “Asian woman” connotations of Peter Hall's 2002 Bacchai, in which the chorus continuously wrapped and unwrapped themselves in lengths of red cloth, conjuring up images of women in saris and in burqas only to reveal scantily dressed female bodies in salacious poses beneath. As one reviewer of Hall’s production comments, “we are left pondering whether Pentheus is alone in equating Bacchic ritual with immodesty and sexual licentiousness.”12 Instead I see the chorus as part of the world of song, dance, celebration, contradiction, and challenge to established boundaries that the god brings with him. They are forces of liberation and danger, suitable companions for a god “most terrible, although most gentle, to mankind.”13

To those ends, in my Bacchae I make various dramatic uses of the chorus:

First, they have an active role in which, like an "actor," they help shape the unfolding events. As one of the "actors," they constitute a collective character with a clear identity in the fictive world of the play's main episodes.

Second, the chorus also have another active role, more protean and less dependent on their status as "actor." They use their bodies to create special effects such as the earthquake (staggering to convey the heaving earth) and palace collapse (registering it in words and looks) of the third episode. In these examples, the chorus retain their identity of Maenads, but I also use their bodies to simulate the flame on Semele's tomb. With their flame-like movements, my chorus momentarily becomes the flame, an idea that accords well with the conventions of modern physical theatre.

At a more sophisticated level in this active role, the chorus can give visual form to thoughts, desires, intentions, and so on, that are otherwise hidden or can only be inferred. They can also play a part in clarifying the underlying power relations between the figures engaged in the action. Identifying such relations can reveal that social status does not necessarily reflect relative status in interactions among characters. The King, for example, though high in social status, may score poorly in his "status play" with others.14

Third, the chorus may have a more passive role as witnesses, their numbers alone making any interaction of the main figures a public rather than private exchange. They can observe the main action and react to it in various ways, both visibly and audibly. The practical constraints of the mask govern the choices among possible reactions.

Fourth, a masked chorus in particular can establish a focal point through the power of their collective mask gaze, used to direct the attention of the audience. This function is especially useful when there are numerous masked figures present and a sophisticated action to be conveyed. At its simplest level, the collective gaze can identify the person who is speaking when mouths are not visible, and it can clarify what actions and reactions are important. The questions of who says what and who does what to whom are in danger of being obscured by poor mask work, as noted by those commentators on Hall's Oresteia who could not identify the speakers.15 The gaze of even a single mask also has a special power of its own, a phenomenon recognised in ancient Greece.16 This power becomes evident when the mask is turned in full frontal presentation to the audience or to sections or individual members of it. The effect is multiplied in the collective gaze of the chorus (a subject to be discussed more fully below).

Last, the chorus can, in fact, assume the role of the voice of ritual authority in an art form—tragedy—that is a hybrid with ritual elements, rather than essentially ritual. This authority is most apparent in the choral songs, with their philosophical and mythic contextualisation of the main action. In my own staging, the sense of "otherness" that features in ritualistic interpretations such as Hall's Oresteia has its place in the parodos and stasima. But I have also directly evoked the idea of ritual by adding an End Sequence after the concluding lines. Here the chorus take hold of Dionysus, who appears as a plant form in his final manifestation, and pull him apart. Then, using his mask, costume and ivy, they metaphorically resurrect him on a pillar around which they dance in the manner of some of the ancient vase paintings of Dionysian religious ritual.17

Chorus as Actor

In the first episode I use the chorus like an "actor" or collective character who actively participates in the story and interacts with the main figures of the drama. The Maenads, following Dionysus, have descended on Thebes, and when the King arrives they make their presence felt both visually and audibly. The drums to which Pentheus later refers (second episode, Bacch. 51318) are introduced in this earlier scene to enable an audial interaction between King and Maenads in his first speech. This is a monologue of some length (215-262). In my production the chorus are gathered around Agaue's monument (situated upstage left) when the King enters. As his speech begins Pentheus and the chorus interact: they respond defiantly to his words by sounding their instruments, increasingly irritating him. Finally he approaches them with slow menace, and they retreat around the circumference of an imagined orchestra, a circular pathway that both evokes the ancient theatre space and has certain logistical advantages for moving bodies coherently in space without obscuring the audience's sight of the masks. The tenuousness of the King's situation and his response to it are thus given visible form.

In the same scene, the chorus functions as an actor in a slightly different way. Towards the end of his first speech (248 ff.) the King catches sight of Teiresias, who has been standing in a reverie alongside Cadmus at upstage right. Pentheus instructs Cadmus to give up his ivy wreath and thyrsus. In my reading, Cadmus makes as if to comply but Teiresias prevents him, moving him away. The King then delivers the remainder of his speech while backing away from the seer. He now finds himself in close proximity to the Maenads, who (through the chorus leader) deliver lines that support Teiresias (263 ff.) and carry the weight of ritual authority. Pentheus is caught between two bodies of ritual significance, and their combined power places him in a low-status position. He looks from Teiresias to the chorus and then towards the audience, inviting their scrutiny of his thoughts and feelings. The three glances taken together convey his uncertainty. Finally he stalks away downstage to sit on the ground, another move which makes him appear immature and vulnerable. (Precision in gesture and timing—especially in judging the moments when the mask face should be presented to the audience—is part of the special techniques of performing in mask, of which I have given a more detailed account elsewhere.19) In this part of the scene the chorus (now less in the character of wild Maenads than as the considered voice of religious wisdom) is used in conjunction with one of the main figures, Teiresias, to expose subtle shifts of status and to further highlight the vulnerability of the King. The vulnerability of mortals in a world ruled by divine forces is an important theme of the play that I wanted to highlight.

Chorus as Mime

In the same episode, I also use the chorus to make visible Pentheus’ hidden prurient desire when he speaks of the exotic stranger (233 ff). In the production as a whole, the deportment and movement patterns of figures through the space establish gender distinctions: angularity, straight lines, and direct pathways are associated with masculinity, while soft curves and indirect pathways stand for femininity. Usually operating in a "masculine" mode, Pentheus becomes one with the chorus during this part of his speech. They stand close to him, clustered on either side, softly swaying as he joins in and makes gentle curving gestures (Figure 2). His voice also takes on a dream-like quality. An agitated angular gesture signals an abrupt return to his more habitual manner of moving and speaking. In this momentary lapse, the King takes on something of the "feminine" that will be more clearly manifested later in the play.

The chorus also help uncover the underlying power relations that I read into this scene. In my vision, the King displays a certain vulnerability without his guards in close attendance. The latter stand ineffectively upstage while he, in coming downstage, has moved into a space inhabited by forces that threaten his power. He is disturbed by the Maenads and is, through his own predilections, susceptible to their influence, as I have described above. But they give way when he pursues them. The motif of pursuit, realised as a staging device, gives concrete form to one aspect of this status play.

Later in the play, with the arrival of the Second Messenger, I introduce a partial mirroring of the circular pursuit motif of the first episode, this time during the exchange between protagonist and chorus leader (1029 ff.). Now they move anticlockwise and both of them speak, while the rest of the chorus stand to one side observing. My choices here were influenced by the conventions of modern masking, which tends to avoid wholesale repetition unless exceptional circumstances demand it. (Such exceptions might include the need to establish a ritual pattern or a rule subsequently to be broken for comic effect.) Generally speaking, variety is essential in keeping a performance alive; variations on a theme, however, are particularly fascinating and invite linkages and comparisons. This scene can highlight the different attitudes of the King and a member of the city's lower class: unlike his royal master, to whom he appears to be loyal (1032-3), the Second Messenger is able to make allowances for the chorus (1039-40).

In this second circular pursuit motif, the chorus illustrate something of the underlying, complex power relations between Maenads and guards. In giving way to the Messenger, the chorus, represented by its leader, is seen to have lower status than the guards, although her spirited words and his concessive response show that there are opposing tensions. Finally, the chorus’s power to influence the Messenger, that is, to persuade him to stay and give his account when he is about to leave, indicates that this ordinary man is an empathetic being, unlike the King. To enhance this idea, the chorus leader and then the rest of the chorus take hold of his arm to reinforce their plea physically, a gesture he would not permit if he were truly a man of violence.

The attitude of this particular guard compared to that of his King is one that I associate with greater maturity. I have, therefore, given him the fifth-century signifier of mature masculinity by making him bearded. In our production he is also a guard with helmet and costume identical to those of the bodyguards who accompany the King in the first and second episodes. But he wears his helmet on top of his head, revealing that these guards are ordinary working men beneath the sinister garb. He is also the guard who earlier brought on Dionysus and advised the King to heed the miraculous occurrences surrounding the stranger (445 ff.). Again, his understanding of the clearly supernatural nature of these signs may be contrasted with the King's failure to realise their significance. The chorus, in helping to define the character of the Messenger, facilitates this comparison.

In the Bacchae there are two messenger scenes and also narration scenes, which I regarded as opportunities for trying different ways of staging the chorus, as well as for introducing some variety. I first considered having the chorus as an onstage audience, doing little more than listening and perhaps reacting and conferring from time to time as the offstage events are recounted. My next idea, which I used for the Second Messenger narration, was to have the chorus visualise the events so vividly described and join in with some of the partly mimed gestures that naturally occurred to the actor performing the Messenger (Figure 3). It is tempting to imagine that the cheironomia mentioned in ancient sources was employed in this way, an idea suggested by Walton, who envisages a messenger’s words being "fortified by mimetic or atmospheric movement from the chorus to amplify his own stance and gesture".20 In my work on the Bacchae, I found that this second alternative makes the masked chorus appear more spontaneous and childlike, their faces taking on some of the attributes of naive masks.21 In a discussion of the tragic mask, David Wiles speaks of a sense in which the figures of Greek tragedy "see the world as for the first time from a position of naive neutrality",22 a comment that perhaps can only be appreciated when this effect is observed on the mask face.

In the scene where Dionysus describes to the chorus how he tricked Pentheus inside the palace (616 ff.), I again found this device appropriate for the sort of theatre I was creating. Here the chorus starts by giving simple reactions, gestures and laughs of surprise and joy, acting as the perfect sycophantic audience. As the account progresses, they get caught up in the story and join in with some of the god’s partially mimed gestures.

The narration of the Herdsman (677-774) presented opportunities for a more complicated mimetic use of the chorus. Rather than illustrating the Herdsman's account with mimed gestures, I decided to increase the involvement of the chorus and give the scene a boldly physical-theatre treatment by having them enact the scene being described. The Herdsman already has an onstage audience in the person of Pentheus, who moves to a downstage position to one side and settles down, semi-recumbent, facing the audience but with mask partially turned away or lowered. The Herdsman takes centre stage, notionally addressing the King but facing the audience.23The chorus have the remainder of the performance space for enacting the Herdsman's account, becoming the Maenads living idyllically in the mountains, the men planning to hunt them down, the rampaging horde attacking and dismembering cattle, led by Agaue (here without distinguishing headband) (Figure 4). At the end of this enactment there is a regrouping. The text here ("Then they went back/To the place where they had started from"24) seems a signal to switch the choral identity back to that of the here-and-now Maenads of the city. As such, they can now deliver their lines to the King (775 ff.).

In the examples given above, the chorus as actor highlights some of the major dichotomies that feature in the play, namely those of gender, age and class. The distinction between the human and the divine, also a major theme, is clearly articulated in the stychomythic exchange between Cadmus and the god (1344-51), culminating at 1348 with Cadmus' rebuke of the god: "Gods should not be like mortals in vindictiveness."25 Immediately preceding this exchange is the major speech by Dionysus, now appearing in his true form, a text which, though partially lost, has been reconstructed by Vellacott.26 This powerful speech constitutes a climax in the latter part of the play, but for a modern audience it contains many obscure references and may seem overlong. To counteract this effect, my chorus accompanies his words with a disturbing twitching and wailing (Figure 5). My intention is to create a sense of religiously inspired mania and thus to reinforce the contrasting reasonableness of Cadmus in his questioning of the god. Towards the end of Dionysus' speech, the chorus form a menacing group, leaving their previous position at centre stage to approach Cadmus and Agaue. There follows another pursuit motif, now with the chorus as pursuers who surround their quarry and cause them to shift sideways from downstage right to occupy the now unoccupied central space. In their action of "herding" these main figures across the space, the chorus give visual reinforcement to the utter helplessness of Cadmus and Agave in the face of the fate meted out to them by the god.

Chorus as Visual Focus

Through sheer weight of numbers, the chorus is a significant visual element in any scene in which they are present, even when they take no active role. But there are times during the main episodes when the audience's attention should be focussed more on the protagonists than on the chorus, whose collective presence should then be reduced or minimised. Some practitioners use the terms "major" and "minor" to distinguish between performers who should, at any moment, be the focus of attention—”in major"—while all others present are “in minor" and should not be attracting attention.27 The factors determining the impact of the chorus include their configuration in the performance space, the amount of performance energy they exude as a group and whether their masks are facing out towards the audience, inwards towards the action, or elsewhere.

A chorus occupying the centre of the performance space (the equivalent of the centre of the orchestra in the ancient theatre) will command the attention of the audience, as will any figure taking this position. It is here that performers can make the strongest impact on the audience. When in "minor", the chorus should be positioned in weaker parts of the space, where they will compel less attention. If a downstage position is chosen (or, in the ancient theatre, the peripheral part of the orchestra on the audience side), the chorus needs to adopt a low stance in order to avoid obscuring protagonists situated upstage or in a more central position. They could kneel or sit, as suggested by Taplin (see above), or, in a modern production, lie down. Taplin also prescribes that the chorus be as "still and inconspicuous as possible”. But stillness is not necessarily inconspicuous, and it may in fact tend to excite the interest of the audience. Instead of being entirely motionless, the chorus might observe the action, react to it, confer with one another, or be looking elsewhere. None of this should be done in a dramatic manner. In the terminology of physical theatre they should be "playing with a low level of energy."28 Meanwhile, those in "major" should be performing with high energy. This "energy" is not synonymous with activity but refers to the effect achieved by a particular, unaccustomed use of the performer's body. Barba & Savarese speak of the "extra daily body" required for performance and also describe the "retained" energy that is achieved through opposing tensions within the body, for example by a power pushing the body forward and a power simultaneously holding it back.29 Physical-theatre training includes instruction in how performers can realise these tensions within their own bodies.

Mask orientation is an important element in the power of the mask gaze, particularly the multi-masked presence of the chorus. Usually masks are most powerful when in frontal presentation to the audience. In the Bacchae’s fourth stasimon, a choral ode, it is appropriate for the chorus to command the entire attention of the audience. Here I position the chorus upstage initially before it moves downstage in a slow but energised manner, as though approaching and confronting the audience. Here the compelling gaze of the masked chorus is seen, magnifying through weight of numbers the power inherent in any individual mask. Figure 6 shows something of the effect. In another example, when Dionysus is reunited with the chorus in the third episode, I have some chorus members playing in "major" during the chorus leader's speech (612-3) whilst the others together with Dionysus play in "minor". Those in "major" face the audience whilst the chorus members in "minor" turn their faces towards Dionysus and he faces them (Figure 7). These two images cannot wholly impart the experience of being confronted by the gaze of the mask, whose effect can be like a shock wave passing through the viewer's body.30For those who have not been exposed to this phenomenon, an image such as figure 4 can be misleading. In this scene from the Herdsman's speech, masks are shown to work effectively when viewed in three quarters or profile. But the special power of the full mask gaze would be apparent to anyone who experienced it at the performance from which this image was taken. In the ancient theatre, where performers were viewed from many different angles, this powerful gaze could only have been directed to a particular segment of the audience at any given moment, and I suggest that the actors turned from one part of the audience to another, making sure no part of the theatron remained wholly neglected—much as modern actors do when performing in the round.31

This power of the mask gaze can be used to clarify the action in those parts of the main episodes when the chorus is in "minor". When the mask is turned away from the audience towards another mask or masks (or more generally towards an object, another part of the stage, an entrance or exit, etc.), it acts like a spotlight, directing the attention of the audience.32 Figures 8 and 9 illustrate roughly the same moment in the performance. Viewers in a live showing would have seen the feminised Pentheus at centre stage being paraded by Dionysus before the Maenads (Figure 8). All other masks, including Dionysus’, are turned towards the King. Figure 9 shows something of the power of the collective gaze of the chorus directing the audience to the focal point.

In my Bacchae there were two scenes in which I felt the focus should be exclusively on the protagonists: the Cadmus/Teiresias interaction of the first episode and most of the Pentheus/Dionysus stichomythia. In a live performance I would either have placed the chorus in a weak part of the performance space, playing in "minor" with low energy, or have arranged them formally in, for example, two seated lines to the sides, masks facing inward, towards the action. In a circular orchestra, I might seat individual members of the chorus at even intervals around its circumference on the audience side, again facing inwards. In such formal arrangements it is appropriate for the chorus to be motionless, as if part of the architecture. As I was making a film in a limited space, it was simpler to have the chorus downstage to the sides, effectively out of shot. I made an exception in the second Dionysus/Pentheus interaction (642-59), where Pentheus emerges from the palace (or what is left of it after the earthquake). His prisoner, the disguised god, has escaped only to be discovered now, sitting calmly with two of his Maenads directly behind him, the three creating the image of a multiple-armed Buddha. Two members of the dispersed chorus assist the god in his playful goading of the King. With the arrival of the Herdsman imminent, Pentheus looks away upstage, trying to catch sight of him, while the god and his two followers make a sneaky exit, though Dionysus has promised not to run away. The function of the chorus in this staging is 1) to introduce some variety into the Pentheus/Dionysus exchanges (there are in all four scenes of interaction between king and god), 2) to create a compelling stage picture contrasting the god's calm demeanor with the king's agitation and 3) to emphasise visually the slippery and devious quality of Dionysus.

In masked theatre, exits need to be clearly acknowledged visually, with the departing figures in "major" until the audience should cease to notice them. (In the ancient theatre they would either have gone out of sight into the palace or have still been making their way down one of the parodoi). When their exit is no longer of interest, the audience is given a clear signal that the focus of attention returns to the figures still in the performance space, one or more of whom now play in "major."

In the case of entrances when there are one or more figures already on stage, it is usual in modern masked theatre to draw attention to the new arrival, most simply by turning the masks of all those already present to face the point of entry, thus putting them immediately into "major". Even when an arrival is announced in the text, as is usual in Greek tragedy, this direction of focus is still a useful convention in masked or other visual theatre. Not acknowledging an arrival by visual means would leave doubt as to whether the audience is supposed to notice it. Even when the text does not announce an arrival, as with the entrance of the Bacchae's Second Messenger, the arriving character must be visually acknowledged and put into "major", if only momentarily. The figures on stage must be seen to see the arrival before they can be seen to react to it. The idea that figures might enter unobtrusively is nonsense in masked theatre, because a new visual element will always excite the viewer's interest. The point of focus would become unclear and the audience confused.

In my staging of the Second Messenger’s arrival (1024 ff.), the chorus are semi-recumbent downstage, the final position of their choral ode (the fourth stasimon). They turn to face the Messenger as he enters. When the chorus leader speaks, she gets up and addresses him with her mask facing the audience, whilst the others, masks also turned towards the audience, remain lying down. When she has finished speaking, the gaze of the whole chorus returns to focus on the Messenger. This pattern is repeated in the next exchange, before the circular pursuit motif that I have already described.

The giving and taking of focus (looking at the person who is speaking, looking out to the audience when speaking oneself) is a standard device in masking. It is useful, however, to break it from time to time, in order to focus on the reactions of the person listening or just to introduce variety. In the scene under discussion I was employing the device experimentally, trying to see how well it worked with most of the chorus lying down. Although strange, the effect seemed not out of place in a scene preceding the account of the appalling events leading to the dismemberment of the King.

In the sixth episode, when Agaue is giving an account of her hunting (1202 ff.), I seat the chorus on either side of her with masks facing the audience. Having all those present facing out towards the audience will, as I have described, result in a more diffuse focus of attention. But Agaue herself wears a chorus mask, which reinforces her present affinity with the collective identity of the Maenads and completes a stage picture involving all those present (Figure 10). Moreover, although she is outnumbered, she stands speaking and gesturing while the chorus sits still, thereby attracting the attention of the audience. (While masking instantly unifies the visual impact of a chorus, it also highlights any nonconforming actions by individual members).

Cadmus arrives in the scene that follows, and I felt that the focus should be clearly on the interaction between him and Agaue. Here I seated the chorus downstage in two groups facing away from the audience, quietly and attentively watching the action but making no visible reaction until the chorus leader speaks at 1327 f., when chorus faces are turned towards the audience before returning again to the main figures. Throughout this scene the chorus is arranged in two diagonals that clearly direct the audience towards the central action, creating a sort of spotlight effect by means of bodies rather than masks. This is enhanced by the addition of the two guards, who bring the body of Pentheus to Agaue and then stand to attention on either side, looking in at the tragic climax.33

Chorus as Witness

In some scenes I use the chorus, playing in "minor", as a witness to the ongoing events. Far from being an "inconspicuous" presence or a group playing with low energy in a weak part of the space, they now form an important part of the stage picture, clearly paying attention to the protagonists.

In the third of the Pentheus/Dionysus scenes (787-846) that follows the Herdsman's scene, the chorus is out of shot for most of the king/god dialogue but comes back into view towards its end (840 ff.). They sit in two groups on either side of Dionysus with their masks facing the audience, listening and reacting but in an uncoordinated way, like a stage crowd. In the next episode, the feminised Pentheus is paraded by Dionysus before the chorus, which now reacts as a group (rather than a crowd) with masks mostly facing Pentheus. At 963ff. they laugh and confer with each other, masks turned towards the audience. They are now the jeering Maenads whom Pentheus, before his transformation, had at all costs wanted to avoid (842), but they are also a proxy for the citizens of Thebes whom Pentheus now wants to impress (961-2). As Dionysus delivers his parting words, the chrous grow stiller, watching intently, their masks turned towards the departing god. They make no gesture of reaction but merely “witness” with great energy.

During Teiresias' long speech to Pentheus (266 ff.), I tried a different type of staging. In this scene, where the chorus is essentially a witness rather than a participant, I stood the members of the chorus in a formal line upstage left, listening attentively. Throughout the speech they make only one gesture, raising their thyrsoi when Teiresias speaks of Dionysus "brandishing his Bacchic staff",34and at this moment they look directly at the audience. Otherwise they stand still, the gaze of their masks focused on Teiresias. I felt it important not to interrupt the continuity of his speech with too many reactions from the chorus (although the King does react occasionally from his seated position downstage, performing with low energy, lest excessive stillness draw too much attention to him). In other scenes I felt it appropriate to incorporate visible reactions by the chorus to a protagonist’s speech, but for the sake of clarity I chose a few specific moments and had the chorus react as a coordinated group. For instance, Pentheus’ first-episode pronouncement that Dionysus is dead (244-5) seems a good place for the chorus to give a shocked response. Their initial bodily reaction (a fairly naturalistic jerking backwards) is followed immediately by a turning of the masks away from Pentheus towards the audience, accompanied by an enlarged gesture of surprise, before a return of their gaze to the King.

This represents a mixture of what in current theatrical usage would be termed naturalistic and stylised gestures, the former being necessary to make the latter credible. In more general terms, mask has the property of unifying what would otherwise appear to be a disparate range of performance styles. (Unlike the initial, localised bodily reaction, the enlarged gesture would appear melodramatic to modern eyes if performed unmasked). I also mention credibility because the requirement of "truth to performance" is applicable not only to Stanislavskian acting but is necessary whenever an emotional response is to be evoked from the audience. Masked theatre simply achieves it with different means from those employed in the theatre of naturalism.35

Chorus as Ritual

In a somewhat creative interpretation of Plato and Aristotle, David Wiles argues that the former sees tragedy as "in essence a Dionysiac dance"—a ritual with an emphasis on religious, moral and didactic concerns—in which the chorus plays a central role. Aristotle, on the other hand, emphasises the enactment of heroic myth in a way that encourages an emotional response and marginalises the status of the chorus.36 In my own staging of the main action, the chorus does take on the role of "actor", but it also, as I have shown, performs other functions that help to convey the unfolding events. It is largely in the choral songs that I see the opportunity to realise a ritual "otherness" in the choral role. Choral song and dance in English translation, however, is a challenge. The poetry and its specific qualities—particularly metre and vowel sounds (the two most important factors in creating the emotional timbre of a piece)—are of course irreproducible in translation, and the passages of mythic contextualisation are, in meaning and philosophical profundity, quite specific to their own period. Where I felt meaning was obscure (to any but classical scholars) I cut it from the English text but reincorporated a few passages to be sung or spoken by a Greek actress in her native tongue. Otherwise the English text was spoken in unison whilst the chorus performed dance and other stylised movement relating to what I felt to be the "mood" of any particular song and its position in the play. For example, in the Vellacott translation parts of the parodos express ecstatic energy, but there are also passages where the energy of the chorus is more contained. I translated this idea into the language of choreography by means of a rectangular formation (three lines of three) that breaks out and regroups. I also wanted to create the impression of energy without exhausting the performers or risking collisions, an aim made more difficult by masks. My solution was a staggered entry in which the performers run on in their groups of three, stand in formation, and engage in a lively choreographed series of gestures with their thyrsoi, the whole action accompanied by drumbeats. They then break out to interweave and sing, "On, on! Run, dance, delirious, possessed!"37 before regrouping once more. The parodos ends in a tableau with sung and spoken Greek, together with the miming of Dionysus being penned up in the thigh of Zeus.

The first stasimon follows what has been, in my reading, an episode in which the chorus is considerably active and, of course, it is the ode following the energetic entry song. This position itself, together with the "quietist mood of the song",38 suggested a more static and minimal choreography. Members of the chorus, in a tight group, occasionally tilt their heads but otherwise remain still, accompanied by improvised, wordless, ethereal "singing". For the other odes, I found that some passages of the Vellacott translation lend themselves more readily to a rhythmic delivery, and I used these particularly in the third stasimon, which I conceived as a circular dance, with clockwise and anticlockwise movement, ending in a tableau.

There is considerable variety in my realisation of the choral songs, an aesthetic quality perhaps demanded more by our own time than by the ancient theatre. But it is hard to believe that the tragic chorus would have been "straightjacketed", as J.F. Davidson puts it, in a rectangular formation "throughout every song in every tragedy for the entire duration of the fifth century",39a dismal thought indeed! Davidson himself argues the case for a perhaps-less-restrictive circular formation, which I incorporate in two of the odes. However, the modern repertoire of dance/movement presents so many possibilities that I found myself borrowing elements from various more-recent sources, the most arresting perhaps being Yukio Ninegawa's chorus of fairies in his 1994 Midsummer Night’s Dream, rotating on the spot in clockwise and anticlockwise circles whilst standing in strict rectangular formation and, most disturbingly, making jerking movements throughout their bodies.

Conclusion

The dramatic uses of the chorus in my 2010 production of the Bacchae may be summarised as follows:

- as a "collective character" in the story, helping to shape the unfolding events;

- in an illustrative role creating, through bodily movement, effects such as the earthquake and the flame on Semele's tomb, and in accompanying the Herdsman's account by enactment;

- in giving visual form to the hidden desires of Pentheus and also to the underlying power relations in operation;

- in acting as witnesses and reacting in various ways to the interactions of the main characters;

- in creating a clear focal point through the power of their collective gaze, directing the attention of the audience;

- in a role of ritual authority, providing philosophical and mythic contextualisation of the main action and a sense of "otherness", most apparent in the choral songs.

notes

This was a personally funded project, involving two weeks of intensive rehearsal and three days of filming at the Chisenhale Dance Space, London, 7th-23rd April 2010. (Details of the production are available at http://www.chrisvervain.btinternet.co.uk/page12.html.) For this project, in some respects a development of the research undertaken for my Ph.D. at Royal Holloway University of London, I made the masks and props and recruited and directed the actors. The costumes for this production, an integral part of its visual impact, were created by Dr Rosie Wyles (www.Nottingham.ac.uk/classics/people/Rosie.Wyles). I am grateful to David Wiles, Amy Cohen, and anonymous referees for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. Any remaining errors are my responsibility.

footnotes

1 Wright 2000, 20.

2 Csapo & Slater 1994, 54.

3 Taplin 1978, 12-13.

4 Halliwell 1993, 196-7.

5 Seaford 1981.

6 Rehm 1985, 244.

7 Lambert 2008, ch. 8.

8 Easterling 1997, 163ff.

9 Poetics XVIII.

10 Foley 2003, 14ff., 1-2.

11 Arnott 1989, 51 ff.; Walton 1984, 44 and 46.

12 Wrigley 2002.

13 Vellacott 1973, 222.

14 On "status play" see Johnstone 1981, ch. 1.

15 Schulman 1981, Esslin 1982, Walker 1981.

16 Frontisi-Ducroux 1989, 160-4.

17 Some of the "Lenaean" vases, Csapo & Slater 1994, 94.

18 Line numbers are taken from the Loeb edition (Euripides 1938).

19 Vervain 2004, 254-260.

20 Walton 1996, 51.

21 Lecoq 2006, 56 ff.

22 Wiles 2000, 149.

23 Vervain 2004, 256.

24 Vellacott 1973, 218; Bacch. 765.

25 Vellacott 1973, 243.

26 Ibid., 241-242.

27 Wilsher 2006, 62.

28 Ibid., 63.

29 Barba & Savarese 1991, 19, 81, 88.

30 When working with parties of teenage school children it is not unusual to hear gasps of genuine surprise and even fear when they are first confronted by the gaze of the tragic mask.

31 Lambert 2008, 129-131.

32 Vervain 2004, 256-258.

33 Provided by Vellacott 1973, 240 ff.

34 Vellacott 1973, 201; Bacch. 308.

35 Vervain 2004, 258-261.

36 Wiles 2000, 9.

37 Vellacott 1973, 194, 196.

38 Seaford 1996, 182.

39 Davidson 1986, 41.

works cited

Arnott, P. D. (1989). Public and Performance in the Greek Theatre. London: Routledge.

Barba, E. & Savarese, N. (1991). The Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer. London: Routledge in association with the Centre for Performance Research.

Csapo, E. & Slater, W. (1994). The Context of Ancient Drama. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

Davidson, J. (1986). 'The Circle and the Tragic chorus.' Greece & Rome, 33, 38-46.

Easterling, P. E., ed. (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Esslin, M. (1982). 'Review of Peter Hall's Oresteia.' Plays and Players, January.

Euripides. (1938). Euripides III: Bacchanals, Madness of Hercules, Children of Hercules, Phoenician Maidens, Suppliants. Trans. A.S. Way. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press.

Foley, H. P. (2003). 'Choral identity in Greek tragedy.' Classical Philology, 98, 1-30.

Frontisi-Ducroux, F. (1989). 'In the mirror of the mask.' In C. Bérard (ed.), A City of Images: Iconography and Society in Ancient Greece, 147-162, Princeton: Princeton University Press.<

Halliwell, S. (1993). “The function and aesthetics of the Greek tragic mask.” In N. Slater & B. Zimmerman (eds.), Intertextualität in der griechisch-römischen Kömödie, 195-211, Stuttgart: M&P Verlag.

Johnstone, K. (1981). Impro : Improvisation and the Theatre. New York: Routledge.

Lambert, CM. (2008) Performing Greek Tragedy in Mask; Re-inventing a Lost Tradition. Ph.D. thesis, University of London.

Lecoq, J. (2006). Theatre of Movement and Gesture. Trans. D Bradby. Routledge.

Rehm, R. (1985). 'Aeschylus and Performance: A Review of the National Theatre’s Oresteia.' In Themes in Drama. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulman, M. (1981). 'Passion and the Puppets,' A Review of Peter Hall's Oresteia. The Standard, 30 November.

Seaford, R. (1981). ‘Dionysiac Drama and the Dionysiac Mysteries.’ Classical Quarterly 31 (ii) : 252-275.

Seaford, R. (Tr.) (1996). Euripides Bacchae. Aris & Phillips Ltd, Warminster, England.

Taplin, O. Greek Tragedy in Action. London: Methuen, 1978.

Vellacott, P., tr. (1973). Euripides. The Bacchae and Other Plays. London: Penguin.

Vervain, C. (2004). 'Performing Ancient Drama in Mask: The Case of Greek New Comedy.' New Theatre Quarterly, 79, 245-264.

Walker, A. (1981). Review of Peter Hall's Oresteia. BBC Radio 3, Critics Forum, 5 December.

Walton, J. M. (1984). The Greek Sense of Theatre: Tragedy Reviewed. London: Methuen.

Wiles, D. (2000). Greek Theatre Performance: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilsher, T. (2006). The Mask Handbook. London: Routledge.

Wright, J. (2000). “My Theatre.” Total Theatre, 12, Summer, 20.

Wrigley, A. (2002). 'Review of the Royal National Theatre's Bacchai.' JACT Review, Autumn.