Orestes Terrorist

Translated and Adapted from Euripides' Orestes by Mary-Kay Gamel

Directed by Danny Scheie

Music by Philip Collins

May 20–29, 2011

Presented by the Theatre Arts Department

Mainstage Theatre, University of California, Santa Cruz

Review by Fiona Macintosh

University of Oxford

Annie Ritschel as Elektra, Ethan Donoghue as Apollo, and Keith Burgelin as Orestes

Photo: Steve DiBartolomeo, Westside Studio Images, Santa Cruz, CA.

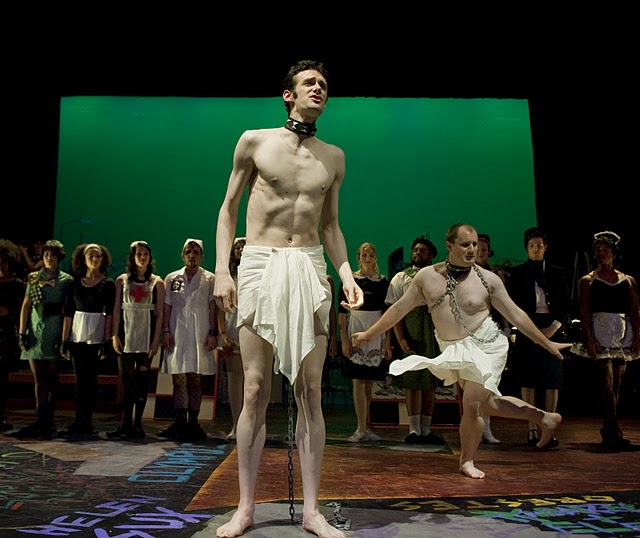

Jesse Buddington and Zackary Forcum as the Phrygian Slaves

Photo: Steve DiBartolomeo, Westside Studio Images, Santa Cruz, CA.

For three weeks in February 1968, the then little known Orestes by Euripides was staged in William Arrowsmith’s translation in the Durham Theatre on the Berkeley Campus of the University of California, with students from the Drama Department. The director was the Polish intellectual and literary critic, Jan Kott, whose recent comparative study of Orestes and Hamlet had led him to the Orestes in Euripides’ disturbing study of the mania of the avenger. Kott, a visiting Professor in the Drama Department at Berkeley, had lived through the horrors of World War II, negotiated the perils of the Stalinist years and had recently resigned his Party membership. He knew exactly what life in Elsinore under Claudius was like; and Argos after the Trojan War, and Athens in 408BCE, were equally familiar territory. Arriving in California in the Fall of 1967 he had witnessed the repressive establishment reprisals during the Oakland anti-draft demonstrations, and in his production ugly scenes from the events, together with documentary footage from Vietnam, were projected onto the backdrop. For Kott, it was the chorus that mattered: not just in its relationship with the other characters in the play, but also and especially in relation to the audience. The use of speakers and pre-recorded material made his production a kind of Happening, in which Argos merged with Washington DC. The chorus (multiracial, male and female) were dressed like Berkeley students, whose movements enacted the lyrics delivered by an anonymous male voice, relayed via the speakers, to the music of John Cage. Their Brechtian-style message was bitter and harsh; the violence of the language was matched by visual discordances as when Menelaus burst through the screen stepping on the image of a killed Vietcong. At the end of the play, Apollo appeared as a 15- foot copy of the Statue of Liberty, with a bikini-clad Helen on its pedestal, before the chorus were reduced to automata, dancing to the strains of ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction’.1

Equally topical is Orestes Terrorist, performed this May on the Mainstage Theater of the Theater Arts Center on the Santa Cruz Campus of the University of California. This new and creative version by the classical scholar, Mary-Kay Gamel, directed by Danny Scheie, with music by Philip Collins and performed by the students of the Theater Arts program, speaks urgently to contemporary western anxieties and concerns. The play opens upon a graffiti-ridden set, disfigured with barbed wire fences and strewn with debris, within a state riven with civil war, imminent or actual. The choice of title, Orestes Terrorist, with its omission of the definite article, is both striking and significant. For in Gamel’s version we witness a violent world in which almost everyone is cast either as instigator, perpetrator or colluder in the violence. Here the divine machinery (read the western superpowers) has set a chaotic and internecine plot in motion; and unusually for modern productions, the divine machinery assumes a centrality within this production. Apollo (Ethan Donoghue) appears with each mention of his name and yet he is too busy philandering (his first appearance is in flagrante with a nurse) to reveal any higher or purposeful plan. The disaffected and thoroughly dangerous generation of mortals that ensues (read Bin Laden and his followers) lurches from one bloody plot to another in an effort to exact revenge on their erring elders (read Middle Eastern despotic rulers) and then effect their own escape and survival. Orestes Terrorist, like Euripides’ Orestes, is unerring in its insistence on the collective nature of the frenzied action on display: Orestes doesn’t so much act as is acted upon, first by the Furies, then by Pylades (who suggests Orestes try self-defence in the Argive Assembly and when that fails, that they kill Helen and become national heroes) and finally by Elektra (who suggests the kidnapping of Hermione before she dons a suicide jacket, with which we infer she will bring about not only her own death but that of her brother and their co-conspirator as well). When the white-suited Apollo appears ex machina at the end of the play, his suave solutions are as imperious and empty as those pronounced by the superpowers who act on the world-stage.

Where Kott drew on avant-garde models – Brecht and the Happening – Gamel/Scheie/Collins turn unashamedly to popular cultural forms such as the modern musical (Sondheim, Lloyd-Webber) and contemporary dance and musical genres (there is an exhilarating hip hop number during the murder of Helen, which implicates the audience absolutely in the avengers’ amoral web). In a world of utter spin, it is not just the politicians like Menelaus or those would-be politicians like Orestes who seek to censor reality: here the Fox News-style reporter, ingeniously substituted for the Greek messenger, deftly manipulates the citizens in the Assembly eager for celebrity so that he adroitly shapes the outcome of the trial. As with Euripides, the increasingly frenetic nature of the protagonist and his co-conspirators is matched by stylistic disjunctions: the exotic Phrygian slave’s monody, for example, is effected by a sharp shift in musical idiom from the demotic to the baroque, with an aria sung by the counter-tenor (Jess Buddington) to the accompaniment of a balletic enactment (comically yet poignantly) executed by his fellow slave (Zackary Forcum).

This is a high energy, action-packed, anarchic, deliberately messy and pacey Orestes, where the youthful chorus steal the show with their punk-style irreverence, insouciance and vibrancy. Three chorus members (Zackary Forcum, Areyla Moss-Maguire and Jenna Purcell) were responsible for the choreography – quite some feat that paid off particularly well in the parodos, where the Furies (absent in Euripides) are physically present and truly terrifying in their assault on Orestes, from below, above and around, as he is ensnared on the bottom bed of a battered bunk bed. What contributes most to the energy of the piece is the highly creative use of the stage space: just before the magnificent aerial appearance of Apollo and the scintillating Helen (played by the stunningly beautiful and plausibly devastating, callous, and uncaring Brie Michaud), the transmogrified, frenzied trio of Elektra, Orestes and Pylades, with Hermione as hostage held at knife point, fall into the wire mesh that shields the lighting gantry over the audience’s heads. These terrorists could literally blow the roof off the building; or, worse, fall on top of the audience, taking us down with them.

As well as a punchy chorus line, musical theatre needs stars, and Elektra (played by Annie Ritschel) is a star in the making with a strong and impressive vocal range. Less secure are the leather-clad duo Orestes and Pylades, whose nascent homoerotic attachment in Euripides is here developed into a fully-fledged attachment, given full rein in a purgative sexual encounter in the onstage shower following the murder of Helen. Elektra’s incestuous attachment to her long-lost brother, and her betrothal to her brother’s lover, are elaborated in a three-way erotic encounter fuelled by the excitement of revenge. These privileged but abused, haughty yet fragile, educated and still profoundly irrational young people provide ample evidence of the damage wreaked on young lives reared under politically repressive states. Gamel/Scheie, like Kott some forty-three years previously, has found an Orestes for our times.

footnote

1 Jan Kott and Bogdana Carpenter, ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction’ The Drama Review: TDR 13 (1968): 143-149.