Visual Resources

The Theatre of Pompey

By the THEATRON consortium

The location of the theatre today

The location of the theatre today

In 55 B.C. the triumphal general Pompey the Great persuaded the authorities to allow him to construct Rome’s first permanent theatre -- the largest the Romans ever built, anywhere - and to name it after himself. This was no ordinary theatre, and it has long fascinated and intrigued scholars. It served as the prototype for the many hundreds of theatres which the Romans constructed subsequently, throughout their empire.

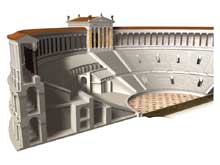

The stage of the Theatre of Pompey was enormous: almost 100 metres wide. The scaenae frons was several stories high probably rising to the level of the top of the cavea opposite. It was sumptuously decorated with architectural embellishment, statues, and every variety of ornamentation. It could be used as a visual and architectural form of propaganda impressing the spectator.

Immediately in front of the stage was the orchestra. In Roman theatres this space was rarely used for performance (unlike Greek practice, in which the orchestra was frequently used by the chorus for dancing). Instead important Roman officials, including members of the Roman Senate, magistrates, and Priests had seats of honour here. The first 14 rows of the cavea (which rose in concentric rows upon the level space of the orchestra) were reserved for Roman 'knights'; members of the Equestrian order. Above them, the remaining rows up to the very top of the cavea were assigned by law to specific groups and classes of spectators. Foreigners, slaves and women were allowed to watch from the uppermost gallery at the back. The auditorium and its arrangement thus served as a microcosm of Roman society.

At the rear of the auditorium stood a temple dedicated to Venus Victrix. This was Pompey’s 'patron' goddess to whom he credited the success of his military campaigns. According to one tradition, by placing the temple on top of his theatre, Pompey ensured that Rome’s first permanent theatre would be allowed to remain because of its religious association. Apparently this temple was constructed so that the monumental ramp of steps leading to it formed the central bank of seats in the auditorium. It was said that when Pompey’s political rivals objected to a permanent theatre, he claimed that he was building a temple beneath which steps would be provided for watching the games in honour of the goddess. (Tertullian De. Spect. 10) Earlier Roman theatres, although sometimes very elaborate, had been temporary and were dismantled after the particular festivals in which they had been used.

The circumstances do indicate the continuing integration of theatrical performance and religious rites, which had been practised by the Greeks, including the close physical proximity between theatre buildings and religious shrines. By sanctifying his theatre with a temple dedicated to the goddess to whom he credited his military victories, Pompey both avoided any quibble about whether the provision of such a building was an appropriate benefaction from a triumphal general, and ensured the survival of a 'private' monument glorifying an individual in a manner never before practised in Rome.

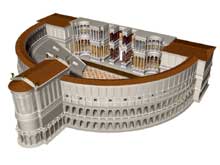

The 3D reconstruction of the Theatre of Pompey below, created by Martin Blazeby at the 3D Visualisation Centre, the University of Warwick, is based on the drawings of the Italian archaeologist and architect Luigi Canina (1795-1856).

(click on the images to expand)

|

|

|

|

| View of the exterior | View of the frons skene | View of the Temple of Venus | Architectural cut-away |

Images copyright the University of Warwick. Created by the THEATRON Consortium.

For more information on THEATRON please visit www.theatron.org